UPDATE: After a public hearing on May 14, the Landmarks Preservation Commission denied the undermentioned application to preserve the facade of the building, while demolishing and reconstructing the rest of the house.

BY EILEEN STUKANE | Save Chelsea, an organized coalition of Chelsea’s community groups and residents, is dedicated to preserving the history and beauty of Chelsea’s buildings—places that hold stories of the past, secrets of generations long gone.

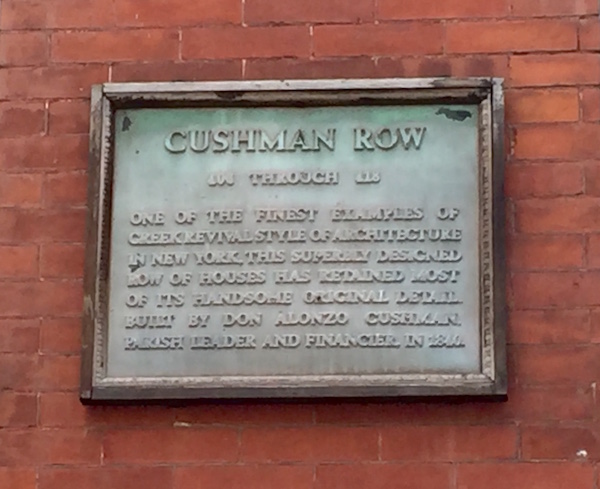

These houses are more than brick and mortar. They are the soul of the community, which is why, in these early days of May, members of Save Chelsea, along with members of Community Board 4 (CB4), are alarmed. A prized stretch of history, the seven glorious, unified Cushman Row houses from 406 to 418 W. 20th St. (btw. 9th & 10th Aves.)—built in 1840 by Don Alonzo Cushman for his daughters, and in the heart of the Chelsea Historic District—are at risk of being compromised.

The new owner of 418, David Lesser, Chairman and CEO of Power REIT (Real Estate Investment Trust), who also holds executive positions at other investment companies, has applied to the NYC Landmarks Preservation Commission (LPC) to make significant changes, which would set 418 apart from its sister Greek Revival homes, and continue a contagion that has already infiltrated the Chelsea community—Facade-ism—which is spreading throughout the city.

The LPC stipulates that with landmarked buildings, facades must remain historically accurate—but everything behind a facade seems up for grabs. Chelsea’s preservationists hope to broaden the LPC’s historic interest to include the entire perimeter of a building.

At its May 1 full board meeting, CB4 approved a letter to LPC chair Sarah Carroll, requesting a denial of David Lesser’s application for demolishing everything but the facade of the five-story building and the front roof slope. The rear roof slope and rear wall of the building, with its wood-framed tea porch, would be demolished. A new, lower cellar would be constructed to extend beyond the existing cellar, over 29 feet from the main rear wall of the house—and new basement, first, second, and third floors would extend out at various distances into the rear yard, breaking with the ensemble look of Cushman Row from the back.

Save Chelsea has written its own extensive letter to LPC’s chair to support CB4’s letter, but also to highlight the point that Chelsea’s historic homes are being purchased, not by families to live in, but by real estate developers who see products to revamp and sell.

The LPC has scheduled a public hearing on Tues., May 14, with the 418 W. 20th St. proposal on the agenda. Specific time for addressing this agenda item will be posted Fri., May 10, here: www.nyc.gov/landmarks.

Is History Only Six Inches of Brick?

Sparing a facade while taking down the rest of the building cannot continue unchecked, say Chelsea preservationists. To understand this quirk of the LPC, I accepted an invitation from Save Chelsea members David Holowka, Pamela Wolff (First Vice-President) and Sally Greenspan (Press Liaison), to join them on a walk through Chelsea’s Historic District. (Holowka is also a member of CB4’s Chelsea Land Use Committee, and Wolff is a public member of CB4, who also sits on the Land Use Committee.)

We met in front of 460 W. 22nd St., an 1840 townhouse that has become a cautionary tale. It is perhaps the first time a landmarked house in the district has been completely gutted, expanded in the back, and flipped.

Pamela Wolff was chair of CB4’s Land Use Committee at the time the house was purchased for $4.6 million by owners Bill White and Bryan Eure in 2012.

“They came to the Committee and they were anxious to have approval,” says Wolff. “They presented, not that they were going to totally demolish, but that they were going to do interior work and do a little extension off at the basement level to the rear. This was being done because Bryan Eure’s parents were getting older, and they needed to have to have a place to provide them to live. They were all going to live in that building, and Bryan and his husband were going to take care of the elderly parents. That’s why they wanted to do the renovation work, change the floor levels, install an elevator.”

CB4 gave its approval, and so did the LPC.

What followed was another application to the LPC, one that did not require a public hearing, which stated that the rear wall of the building was unstable and needed to be totally demolished. The end result is, while the facade of the building remained the same, there is a new house behind it, a house that White and Eure did not move into with elderly parents. Instead, they sold it for $16 million in 2014, two years after they had purchased it. As reported by the New York Times (12/21/2014), the basement is an entertainment/media center with heated slate floors, and the roof terrace has an outdoor shower and whirlpool bath.

When History Becomes Hot Property

This experience has put Save Chelsea’s members on alert to the ways in which history can slowly disappear. Walking from W. 22nd to W. 20th St. and Cushman Row, Holowka commented on how speculators rather than homeowners are purchasing historic houses, because proximity to the High Line has increased the value of nearby Chelsea real estate.

“How much additional area the LPC will approve goes into their financial calculation,” said Holowka. “Then they buy the place, Landmarks lets them tear down everything but the facade, blow out the back, put in one of these huge basements, and what happens is that the historic profile of the entire block gets brought into that. The open space [in the back of the house] is lost, and the reality is transformed, except for what a passing tourist can see. That was never the idea of what historic preservation should be.”

The Oldest House In Chelsea, at 404 W. 20th St. is not part of Cushman Row, but it is the eastern anchor of the row, and it has set off another Facade-ism alarm, as the LPC has given its approval for the building’s history to be erased.

Standing in front of 404, Holowka explained that the land upon which W. 20th St. (btw. 9th and 10th Aves.) was created was owned by Clement Clark Moore, the well-known author of A Visit from St. Nicholas, who inherited the Dutch farmland purchased by his grandfather in the 1700s. In 1830, Moore allowed a man named Hugh Walker, who was renting the land that is today’s 404 W. 20th, to build a two-story house—with the stipulation that it have a brick or stone facade (a third floor was later added). It was Moore who also provided his wealthy friend Don Alonzo Cushman with the land for Cushman Row.

One can still see the wood clapboard siding of 404, on view due to the existence of the historic alley of the house. The house had been cared for by its owners, longtime Chelsea residents Lesley Doyel and her husband Nicholas Fritsch (who have since departed the neighborhood). They had been known in the community as preservationists. In fact, Doyel had been a president of Save Chelsea. According to my tour guides, when Doyel and Fritsch put the house on the market in 2015, assumptions were made within the community that it would be sold to a new owner, one who would preserve its historic importance, just as they had.

When 404 was purchased for $7.4 million by Ajoy Kapoor, a private equity manager and investor based in England, founder of Velocity Capital Advisors and Saffron Capital Advisors, he quickly moved to obtain LPC approval to reconstruct the property.

An application was made to the LPC to turn the house into a “megamansion.” Architectural plans were drawn up by William Suk, of Suk Design Group—the same architect who recreated 460 W. 22nd so that only the facade remained. Once again, the plan was to do a complete rebuilding. Also reminiscent of 460, the “elderly parent” story reappeared, when Kapoor reportedly said his elderly mother would be living there with him, his wife, and son, and he had no plans to flip the house.

As we continued to study the historic house, Holowka noted that structural instability was cited in the application as a reason for rebuilding. The neglect and structural instability of the building—a bulging sidewall along the alley (which we could not detect), for example—was disputed by the former owners and LPC’s own deputy counsel. The community, along with elected officials, protested in letters, and a rally was held in front of 404. Still, the LPC granted the requested changes. The oldest dwelling in Chelsea now has LPC approval to be gutted, to lose the alley, to have the back of the building demolished and rebuilt in glass-fronted tiers stretching out into what is now green space, and to have a massive lower level for entertainment. The house, to be rebuilt in steel and brick, will have only the facade preserved.

With all of its LPC approvals in place but no changes made, today 404 sits empty and quiet. Contrary to what Kapoor said, he put the house, which he never occupied, up for sale twice. According to realtor.com listings, in May 2018, it was listed for $10.5 million. In October 2018, it was listed for $9.9 million (it is unclear whether it remains on the market).

A plaque which read “Oldest Dwelling In Chelsea, Frame House With Brick Front, Built in 1830” had been installed in the brick to the right of 404’s front door. It has been removed. Four holes, where bolts secured the plaque, are what remain.

All this leads up to questions about whether the LPC will grant approvals to the application for changes to 418 W. 20th St. and historic Cushman Row, seven charming 1840 brick townhouses with 10-foot front yards, ornate original wrought iron handrails and guardrails topped with palmetto crests, attic windows encircled by laurel wreaths, and tea porch architecture in the back—preserved examples of Greek Revival design. For Chelsea’s community groups, next week’s public hearing is crucial to the existence of its historic district.

Cushman Row in the Crosshairs

West Chin Architects have created the design plans for the renovation and rebuilding of 418 W. 20th St., but these plans are remarkably similar to those for 404. Save Chelsea’s letter to the LPC states: “The proposal for 418 in fact closely parallels that of 404. The owners of both houses are professional real estate developers. As with 404, the owner of 418 proposes to create additional floor area by excavating under and behind the existing cellar, blowing out the back of the house, and projecting into the rear yard. The resulting building would substantially deviate from the scale of the original house and greatly reduce rear-yard open space, light, and air—character-defining features of the block’s open core.”

The facade would remain. As the Save Chelsea letter also notes, “The house is being treated as a teardown for a larger, modern replacement. There will be no original building left to be added onto, just a façade that acts as a commemorative plaque to the authentic history that once stood behind it.”

If the uniform historic quality of any one of the Cushman Row ensemble houses is compromised, the further concern of Save Chelsea is that the rest of the houses will be at risk.

The LPC’s past approvals were granted under its former chair, Meenakshi Srinivasan, who resigned in 2018 after dozens of neighborhood and historic preservation groups called for her to be replaced, following her proposed rule changes for landmarks. In September 2018. Mayor Bill de Blasio appointed Sarah Carroll the new chair of the LPC, where she has worked since 1994. The mayor listened to the calls of communities to name a preservationist to the post, and that is what Carroll is. She has a master’s degree in historic preservation from the Savannah College of Art and Design.

My walking tour guides of Save Chelsea are hopeful, but hardly naïve. Their preservationist positions are guided by what has already happened to historic houses in the neighborhood. They are fighting to protect the community they love. They are determined to help Cushman Row remain intact for far more than the almost 200 years it has already survived.

Chelsea Community News is made possible with the help of our awesome advertisers, and the support of our readers. If you like what you see, please consider taking part in our GoFundMe campaign (click here). To make a direct donation, give feedback about the site, or send a Letter to The Editor, email us at Scott@chelseacommunitynews.com.

Pingback: naza24

Pingback: ราคาบอลวันนี้

Pingback: Counterfeit Canadian dollars

Pingback: Noord-Brabant Limburg Zeeland Online medicatie kopen zonder recept bij beste Benu apotheek alternatief

Pingback: go to these guys

Pingback: เบต้าเอ็กซ์

Pingback: pay debt

Pingback: browse around this web-site

Pingback: this

Pingback: mp3 juices

Pingback: gas powered drift rc cars

Pingback: buy chiappa guns

Pingback: สล็อตเว็บตรง

Pingback: buy mushrooms online for sale mn

Pingback: thc gummies online

Pingback: cheap liquor for sale

Pingback: slot online

Pingback: nova88

Pingback: Buy Non-Typical 450 Bushmaster

Pingback: buy kurupts moonrock for sale Oregon real estate,

Pingback: contactos mujeres

Pingback: psilocybin capsules for sale

Pingback: legit dumps cc

Pingback: joja87

Pingback: it danışmanlık ücretleri

Pingback: audit instagram account

Pingback: HP Servis

Pingback: carpet cleaning services

Pingback: free game

Pingback: adsl teknik servis

Pingback: microsoft exchange kiralık sunucu

Pingback: https://ighacker.org/

Pingback: On Cushman Row, a Win for Preservationists and Historic Districts – Chelsea Community News