BY DONATHAN SALKALN | It’s a shock to system when a friend suddenly dies—snatched in an instant. Missed opportunities to exchange gossip and opinions, to share a meal, a wine or beer, a smoke, or to forgive or be forgiven.

Judy Richheimer was such a friend of mine, and to many others. She died on Friday, March 27, at Lenox Hill Hospital, of complications from the coronavirus. She is survived by her brother, David, his wife, Aniko, and their daughter, Stephanie, and son, William.

I think of Judy as a beatnik bohemian alley cat. She was fiercely private, aloof, elusive, and always articulated in her beatnik way—center stage. She rarely backed down from a catfight, often taking the opposite end of an argument just for the sport. Her progressive claws never tired. And, like an eccentric feline, one moment you’d be warmly talking to her, she, seemingly purring, and then she would disappear, unheard for weeks or even months. She was also very much bohemian—one definition being: Those who often prefer the company of likeminded people, with few permanent ties, involving musical, artistic, or literary pursuits.

During the nights, the alley cat part of Judy strayed, roaming the back alleys of historical, political, park, judicial, and art programs. She enjoyed the life of scouring the city for free knowledge—and New York City, with its diversity, fed her, and fed her well. Along the way, Judy would join others in fighting for needy causes. Judy tried to remain relevant in an age where cerebral was slowly being replaced by virtual.

Much of Judy’s argumentative prowess and her disdain for the wealthy came from the dinner table of her childhood in Flushing, Queens. Her teenage years were the 1960s, when the country was in cultural and racial upheaval. The war in Vietnam, Martin Luther King, and the women’s right to choose were the rage of the progressive. Judy’s domineering father, Leonard, a dedicated internist/cardiologist for most hours of the day, would lace the family’s meal (mostly prepared by a maid) with demands of perfection directed at both Judy and her older brother, David (of three years). Their father often cited a cousin whom he felt was a model student.

“Our dinner was always a battlefield,” her brother recently said. “Our dad was a bossy doctor. Mom tried to settle things, but was not always successful.”

In explaining their father’s work ethic, recalled David, “Recreation for dad was reading medical journals.” Their father would, he noted, “sometimes sneak into our wing of the house, from his attached practice adjacent, and enter Judy and my rooms to make sure we were working. Perhaps that explained our dislike of homework-type assignments, and abiding need for privacy.”

David, a self-described Kennedy Democrat and Eisenhower Republican, was sent to Wilbraham Academy Boarding School near Springfield, MA, leaving Judy alone to fend off her father’s tirades, and go clothes shopping in New York City with her mother. She gained political experience as class president of Junior High School Daniel Carter Beard 189Q (Flushing). Much of her time at Bayside High School was spent in the theatrical department. Her parents sent her to France for an extended trip.

While her brother attended University of Rochester, then University of Michigan Law School, Judy went to New York University School of the Arts, studying both acting and film production. While a student, she was arrested for painting graffiti. While most graffiti artists painted short graphics or signatures and ran like hell, Judy was apprehended for painting a rather long message: ”NIXON AND AGNEW, YOU BETTER START SHAKEN’, BECAUSE TODAY’S PIGS ARE TOMORROW’S BACON!” It was a time in history when protesting ended with bad consequences, and the wrath of NYU was no exception.

Judy moved to Chelsea’s London Terrace in the 1970s. Early on, she produced and directed educational filmstrips for Guidance Associates and Prentice Hall. Topics focused on American history and social and cultural life.

During her 40 years as a journalist, Judy’s stories encompassed culture, civic affairs, arts/entertainment, and business. Her notable interview subjects included Eric Bogosian, Norman Mailer, Edmund White, Spalding Gray, and Sonia Braga, and Lani Guinier.

For City Limits, she roamed the courts, writing about judges, and she also wrote an in-depth piece on judicial abuse associated with New York’s Mental Health Courts. Other publications with a Judy Richheimer byline include Details, Vogue, Spin, Publishers Weekly, Hollywood Reporter, Theater Week, Soho Weekly News, and Chelsea Now—where her assigning editor was Scott Stiffler, founder/editor of Chelsea Community News.

“I spoke with Judy shortly after Schneps Communications bought the paper, along with NYC Community Media’s other hyperlocal papers, including The Villager. At the time, she was on assignment for the third article in what would have been an ongoing series (based on a pitch she brought to us). What began as a Chelsea-centric focus on the MTA’s lack of elevators fast became as much about urban planning, activism, ADA compliance, and the moral imperative to meet the needs of the elderly, disabled, and injured.”

Told by Stiffler that new ownership gave no guarantee Chelsea Now’s mission and focus would remain unchanged, “Judy didn’t miss a beat,” recalled Stiffler. “She kept making phone calls, going to meetings and court hearings, gathering facts, and expanding her vision for the series.

On Nov. 1, 2018—less than two months after Schneps took over—Stiffler, who served as Chelsea Now editor for nearly nine years, was let go. “A lot of other editors, reporters, and other longtime staff lost their jobs that day, or would in the months ahead,” said Stiffler. “I called to let Judy know, and give her the new editor’s contact info. Schneps soon cut its per-article freelancer rate in half, and drastically reduced the number of articles dedicated to the people, places, and concerns of a paper’s namesake neighborhood, including that of our sister publication, The Villager.”

Shorty before launching Chelsea Community News on April 22, 2019, Stiffler said he talked with Judy “about Manhattan’s shrinking hyperlocal media herd. She offered to bring her MTA series to my website. I told her what I always did: ‘Proceed ahead as you see fit,’ knowing it could be months between assignment and publication.”

Stiffler said although Judy would check in on occasion, with word of a new source or angle, “She never handed in her crosstown bus-themed article. Like the loss of Judy, that’s a loss for all of us, because I know she would have delivered exactly what I’d come to expect—tough, rigorously vetted investigative journalism that remained fair while boldly advocating for the neighborhood she loved.”

One of her investigative pieces in New York Magazine caught this reporter’s eye: A Sewer Runs Through It. Her story exposed a city plan to situate Hudson River Park beaches adjacent to sewer outfalls.

Judy also worked independently, giving both bus and walking tours. Clients included business improvement districts, including the Lower East Side and Lincoln Square Business Improvement Districts, and the Times Square Alliance. Other clients included The Municipal Art Society, Cooper Union, and the Lower East Side Jewish Conservancy. For years, she was Government Relations committee head of the Guides’ Association of New York City (GANYC), where she took on City Hall on labor issues, bus routing, and zoning and land marking proposals.

Judy once shared with her fellow tour guides, her insights of Chelsea:

“When I moved to Chelsea no one (so to speak) knew where the hell it was —it was that backwater. Today—well, you know… I set up Chelsea in the following way: Think of a well-born lady with a nice fortune, but nothing tremendous. Then she falls onto hard times and has to take a job as a librarian. (Think old-fashioned librarian stereotype, not the hip-looking librarians of today.) Then, after many years of sobriety, the librarian takes a drink—and suddenly, she’s the life of the party! Apropos, stage two: In the book The Age of Innocence, which is set in the 1870s, author Edith Wharton described my block as one that used to be fashionable, but now housed ‘small-dressmakers, bird-stuffers, and people who wrote.’ In other words, home to the non-fabulous.”

Richheimer continued:

“Another literary depiction that pointed to the formerly drab cast to that neighborhood can be found in a Dawn Powell novel, set in the 1940s or 50s. Two of the characters were taking an adult education course in Chelsea, and after class, they wanted a drink. They didn’t for one moment think of a looking for a place in the neighborhood, but instead stuck out their hands, hailing a cab to the Village. When I moved there in the ’70s, socializing in Chelsea continued to remain an oxymoron. You might live in the neighborhood—in those days you could get way more bang for the housing buck than you could in the Village—but you pretty much always traveled to below 14th Street to find cute places to eat and/or drink.”

Politically, Judy did fundraising for the Harvey Gantt United States Senate campaign in 1990, calling lists of potential high-end contributors and securing pledges, several at the maximum level. It helped fund Mayor Gantt’s race against Republican Senator Jesse Helms. Gantt, an architect with a degree in city planning from MIT, was the first African American mayor of Charlotte, North Carolina. He lost, but won 47% of the vote.

In 1992, she did fundraising for the Robert Abrams United States Senate campaign, securing pledges, several at the maximum level, to fund Attorney General Abrams’ race to challenge Republican Senator Al D’Amato. As former Bronx Borough President and Attorney General, Abrams built a reputation as an activist and consumer advocate, taking on environmental polluters, charity frauds, and discrimination in housing. He narrowly lost the election.

Judy also volunteered as a dog walking for a dog shelter. “She loved dogs,” her brother told me. “Yearly, she would visit our home in Connecticut for the family gathering. When dad or others asked too many personal questions, she would take our dog for long walks. After the dog died in 2002, she stopped visiting.”

Her soulmate was a poet, Paul Montazzoli, who died young. In The New York Times of Sept. 17, 2010, Judy memorialized him:

MONTAZZOLI–Paul. August 28, age 58. Son of late Dominic. Survived by companion, Judy Richheimer; mother, Victoria; brother, John. Copyeditor, St. Martin’s. Author, introductions, Barnes & Noble Classics: Wharton’s Summer, Sinclair’s The Jungle, others. Poet. Independent scholar: Early Music, silent film. Civil libertarian. Biting wit, trenchant mind, and sweet soul.

(Note: A piece written by Montazzoli follows this story.)

Another dear friend was Frank Wilkinson, an editor, and author of the book Bygones. As a past District Leader representing the Upper East Side and a longtime member of the Four Freedoms Democratic Club, Frank would often run into Judy at various judicial events, and they became steadfast. Judy once invited me to the Three Parks Independent Democrats picnic, where I met Frank, and the three of us sat on a park bench up on a hill overlooking the festivities, eating Southern fried chicken, while Judy and Frank caught up on the latest gossip. I learned that they often met up at various events and even went dancing.

“Judy loved to dance,” Frank recently told me. “I always wished she would wear heals but she said she had ankle problems. I was six-six, now six-five,” said Frank, laughing. “She often quoted passages from my own book to me.”

Longtime friend Linda Longstreet, who recently stepped down as corresponding secretary of the Chelsea Reform Democratic Club (CRDC), recently explained to me that they shared a love for Chinese food.

“I first met Judy in the Chelsea Cottage [now a Roqa]. She was always sitting alone, reading the New York Times and drinking a tea. She would be taking up a whole table and when it started getting crowded, they would tell her she had to leave, and then she would order some small dish,” Longstreet recalled, adding, “I had worked for Vogue and Butterick Patterns. She always dressed fashionable. We became friends and she introduced me to the CRDC… She was an unusual type person, which I like. She had different friends that seemed to feed different parts of her personality. What was annoying was, she always seemed to take the opposite view of anything you said.”

This reporter first came to know Judy in 2009, when she was Executive Vice President of the CRDC. I had been attending then-president Lynn Kotler’s meetings and received a postcard in the mail announcing an intriguing speaking event: Tom Robbins, the renowned Village Voice columnist, who had resigned in solidarity with laid-off Voice columnist Wayne Barrett. The meeting, held at Chelsea’s Hudson Guild, had an intimate turnout—and up popped Judy as the meetings emcee. Judy wrote a glorious intro for Robbins, and also spoke about the Internet’s strain on a print writer’s livelihood. I enjoyed the meeting and left it feeling lucky I had attended.

In 2010, when Kotler was elected as a Judge to NYC Civil Court and was required by the CRDC constitution to step down, Judy became president, always pushing the pride of the CRDC to the far left.

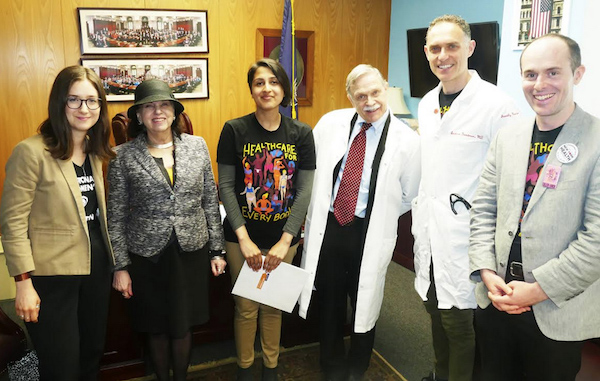

Over the years, Judy ran programs whose featured speakers included the ACLU’s Ira Glasser, discussing the war on drugs; NY State Assembly Member Richard Gottfried and (at that time) New York State Senator Tom Duane, on the need for universal health care (Gottfried, a few years later, would return to speak about his sponsorship of the New York Health Act); Andrea Goldwyn, Director of Public Policy, New York Landmarks Conservancy, on Bloomberg’s rezoning proposal for Midtown East, which threatened landmark-quality buildings; Gallery owner Paula Cooper, on the joys and challenges of running a small business in Chelsea; Steven Barrison, of the Small Business Congress, on commercial rent control; Karen Charman, of the journal Capitalism Nature Socialism, discussing why Nuclear Power can’t solve the climate crisis; Lawyer Tim Swain and Common Cause’s Susan Lerner, on Bloomberg’s term limit extension; Manhattan Community Board 4’s Lee Compton discussed Hudson Yards as the new battleground; Chelsea resident, activist, and journalist Andy Humm, on LGBT liberation within the context of 2013; Big Apple Coffee Party representatives, on their quest to overturn the Supreme Court verdict that favored Citizens United, and ushered in Super PACs. Other programs brought attention to the Small Business Survival Act, and affordable housing.

Judy wrote wonderful introductions. Below is one she wrote for friend and Judge, Arthur Engoron, when he spoke to the CRDC:

“Now this is the kind of jurist I really like! Arthur studied English Literature in college, Columbia to be exact. And he spent seven years teaching classical piano and playing Rock & Roll. Also of interest is that he got his J.D. from NYU and practiced commercial litigation for four years. Then he clerked for New York State Supreme Court Justice Martin Schoenfeld, and in 2002, was elected to Civil Court. And just a few weeks ago, proving that a background in the arts does pay off, Arthur was elected New York State Supreme Court Justice. Congratulation, Arthur.”

During her CRDC programs, Judy would sometimes roam the Hudson Guild’s Carpenter Room wearing a big smile, brushing by many of those standing in the back, like the event’s photographer and reporter (me), and the many electeds, staffers, and CRDC club execs, all whispering amongst themselves or listening to the program. Judy glowed as she walked the room, proud that she had brought another progressive program to Chelsea.

Judy was a procrastinator. Those wonderful introductions for the CRDC’s guest speakers would be finished at the last possible moment. I should know that, as I was her personal IT guy, and printed them, because her printer never worked. Neither did her phone. Her TV’s cable remote relays always got screwed up, and I would have to reprogram the devises to get her Turner Classic Movies back. One such calamity turned into watching the entire movie The African Queen (where I felt she saw me as the Humphrey Bogart character). Her computer was so outdated in accepting modern applications that I bought her a new PC for her birthday, which led to more complications not needed to be spelled out.

Judy and I loved to tell stories, argue, and read the paper together. We often went on bus trips to Albany pushing many causes. Sometimes it was by accident, showing up to board and seeing each other, and other times it was planned. We also sat together on bus trips to New Jersey and Pennsylvania, canvassing door to door for both of Obama’s runs, Hillary, and most recently Democratic candidates in flipping congressional seats.

One recent trip together, I was paired up with Judy to canvas a large neighborhood in southern New Jersey. Big mistake. We were two loudmouths greeting supposedly Democratic-leaning citizens. Normally, I preferred canvasing solo, as people were more apt to open the door to one person, rather than to a group. But this time Judy and I were assigned together. We were given the lists of addresses, and off we went. At each door, Judy would go voice her long, left wing spiel, while never letting me talk.

At one door, I finally butted in and said, “And Andy Kim is only going to back the ban of assault weapons. You can keep all your other guns!” Judy fumed that I interrupted her. We split the remaining addresses, and went our separate ways, me spieling about health care and her, who knows. Yet, no matter how mad you got with Judy, you had to forgive her, as she always forgave you.

On a trip to Albany, I came to find out that Judy was blind as a bat. I was driving a 15-passenger van responsible for picking up a number of doctors and nurses in Westchester and driving them to Albany, for a rally for universal healthcare. I asked Judy to be my navigator. She and I got to talking and missed some crucial exits, and got lost. I realized that she not only couldn’t make out the corner street signs, but also those giant highway signs. We arrived in Albany with everyone before the noon rally, and afternoon meetings with State Senators, but were nonetheless late.

During summers, I would invite Judy out to the family property on Eastern Long Island. I would pick her up at the station, and she would spend the weekend reading on the dock, swimming in the creek, and drinking wine. I found that she had no interest in my gardening, and little skill at cooking, other than mixing a light salad. She did like to lie out on the dock’s lounge and soak in the sun, sometimes wrapped in towels.

Judy loved it out there, except of course, there was that one weekend when the neighbor’s pitched a big tent to celebrate the Baptism of their infant son. Their setup included a dance floor and an amped-up sound system that was playing vulgar rap music. It was afternoon, and the actual party hadn’t begun. Judy, who preferred the lyrics and music of Bob Dylan, got so upset that she stormed the fence, from about 60 yards from where she was reading a book, demanding the neighbors lower the volume. I had begged her not to, but still stood behind her. I saw the pissed-off expressions of three Italian-American generations glaring at the two of us. The music stayed loud.

She was the type of person who never felt she needed to explain her actions. You had to get over that quality of hers to appreciate her.

I tried to set Judy up with friends, but nothing ever clicked.

Judy never wanted the world to know she had wealth stored in growing trusts. She lived the life of a bohemian-beatnik-alley-cat to the end. Yet, no matter how far she tried to crawl away from the trunk of her father’s overbearing materialistic ways, this apple never really got that far from the tree. Both she and her father spent their lives helping the ailing—her father, with a finely directed scalpel, as a doctor, and Judy, with finely selected words and actions, as an activist.

The world has lost more than a voice. It lost soul.

………………………………………………………………………………

A relatively recent letter written by Judy, to a friend:

“On New Year’s Day I did two things unusual for me: 1. taking a cab and 2. giving my card to a complete stranger. The activities were linked.

The driver was old school: white, not foreign-born, sounded like a native New Yorker, and gruff—very. (Sorry, I know that you dislike that intensifier, but for me sometimes it’s indispensable.) I had a blazing headache and the driver’s radio, which was tuned to some kind of sports thing, was contributing to it. My first instinct was to ask him to turn it off, but I anticipated that request could have lead to a headache-intensifying hassle. So instead I took a kind of Zen approach, attempting to charm the driver into conversation—easier on my brain than the radio, I figured.

“What game is that?” I asked. Gruff and Glum responded,”Whadda you want to know for? You follow sports?” “No, just idle curiosity.” I admitted. “Whadda you like? I bet you like literature,” as though throwing down a gauntlet. (His picture could have next to the word “truculent” in the dictionary.) “Why, yes. And paintings and movies,” I replied sweetly. (No need to schlep in politics, with all their provocations.) “Oh, yeah? What was the last silent film you saw and when?” “Broken Blossoms, a few months ago,” I said, lying about the time frame.

At that, he evidently decided to no longer fight with, but to impress, me. It was the end of the ride and he wanted to expound on Griffith and to compare him with Welles. Driver-guy was a bit importunate but pretty interesting. So I gave him my card. A few days later he called and was quite ingratiating; Gruff and Glum no longer. A week from this Sunday is our first date. We’ll see.—JLR

………………………………………………………………………………

Night of the Rebel | By Paul Montazzoli (Judy’s soulmate)

One day—I must have been about ten—I was sauntering along in contented bedragglement when my mother stamped her foot and asked me, “Are you ready to tuck your shirt in and comb your hair and polish your shoes so that other people can respect you and treat you with respect?” I reflected for a moment, then answered matter-of-factly: “No.”

About three years later, I was sitting in catechism class fighting a bad case of the fidgets when Sister Callixta, correctly attributing my unease to hormones, asked me, “Are you ready to reject all sins of impurity – in thought, word, and deed—so that your body will become the unpolluted temple of the Holy spirit and stay unpolluted forever?” I didn’t need to reflect on that one, and yelped out “No!” before her last word was done.

Some time later, returning to the attack, she asked me, “Can’t you see that you’re in need of salvation through Jesus Christ and that this salvation must come through Holy Mother Church?” A smirk this time – and then the No.

One lazy afternoon, just after I graduated from high school, I was settling into an armchair and a book and my newfound freedom when my mother grabbed me with her eyes and asked me, “Can’t you see that you need to get a responsible job and perform it responsibly even if it seems meaningless and is meaningless?” I gave her a somber, level look, and she knew that it meant no.

“Are you ready too” “Can’t you see that –” “Are you sane enough.” My mother and Sister Callixta asked me many questions that started with such phrases, and I always gave them the same answer (which, as often as not, elicited a slap or a blow or an operatic wail).

At last I managed to move many miles away. A new place, a new life. One night I was lying in bed with a woman, thinking Finally I’ve done it! Fallen in love! (I remember the moment exactly: I was curled up on my side, head propped on hand, studying, against the milky whiteness of her window-shade, the silhouette of her belly curving down from her chest), when suddenly she turned and asked me, with a lover’s serious playfulness, “Are you ready to admit you’re in love with me? Can’t you see that you are?” Without reflecting, I gave her a flat no.

Hardly a night has gone by since that I haven’t thought of her . . . of her tears . . . and sometimes that memory leads me to another: My mother telling Sister Callixta right in front of me–“Sister, whatever else we do, we’re going to train him.”

Chelsea Community News is made possible with the help of our awesome advertisers, and the support of our readers. If you like what you see, please consider taking part in our GoFundMe campaign (click here). To make a direct donation, give feedback about the site, or send a Letter to The Editor, email us at Scott@chelseacommunitynews.com.

Pingback: หวยลาว พลัส ออนไลน์

Pingback: fox888

Pingback: แนะนำเกมสล็อตน่าเล่น Naga Games Slot

Pingback: wa dultogel

Pingback: เรียนต่อจีน

Pingback: บับเบิ้ล

Pingback: bangkok tattoo

Pingback: ส่งพัสดุ

Pingback: Saphir Thailand

Pingback: ลวดสลิง

Pingback: Junk search engine

Pingback: กระเบื้องยาง SPC ราคา

Pingback: ทรรศนะบอล

Pingback: ketamin

Pingback: https://soleytour.com/

Pingback: เว็บหวยออนไลน์

Pingback: kojic acid soap

Pingback: Buy DMT Crystal For Sale Perth

Pingback: tiktok video download

Pingback: you can try this out

Pingback: buy howafirearms guns

Pingback: สินเชื่อโฉนดที่ดิน

Pingback: sbo

Pingback: stone display books

Pingback: App Für Erotik Chat

Pingback: kardinal stick

Pingback: prêt hypothécaire 2020

Pingback: trust dumps shop

Pingback: betflik

Pingback: สล็อตวอเลท ไม่มีขั้นต่ำ

Pingback: Business Transformation Strategy

Pingback: Construction Surveillance

Pingback: newsbloger

Pingback: shroomsupply

Pingback: buy magic mushrooms

Pingback: คา สิ โน ออนไลน์ ไม่มี ขั้น ต่ำ