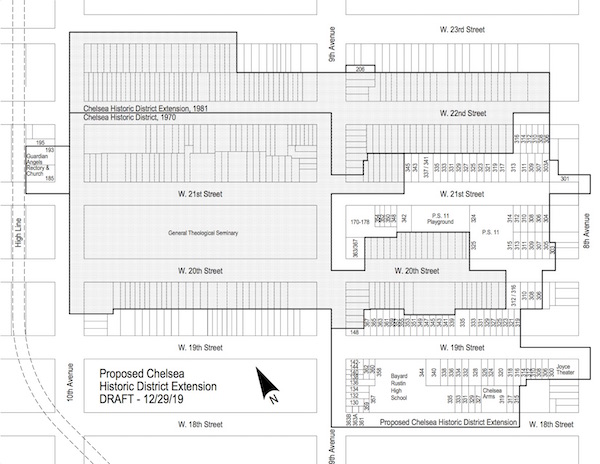

BY WINNIE McCROY | The preservationist coalition Save Chelsea has announced their determination to extend the current borders of the Chelsea Historic District, in order to protect 113 additional buildings they believe have value and merit. If successful, Greek-Revival rowhouses, Federal-style rowhouses from 1835 or earlier, and tenement buildings will be given recognition denied by 1970’s original designation of the Chelsea Historic District, its 1981 extension, and 2008’s designation of the Special West Chelsea District.

“We’ve done an initial survey of the 113 buildings that would be included and have a narrative description that goes with that survey,” said David Holowka, the architect and Save Chelsea board member who is spearheading the move. “The next phase will be examining City records for more detailed information on each building. But that requires going to the NYC Department of Records and the NYC Department of Buildings (DOB), which has been delayed by COVID-19.”

First, Save Chelsea gathered basic information through a visual assessment of the properties, via street view. Currently, they are engaged in the painstaking process of researching each property, including the name of the architect, builder, and owners, the date the building was constructed, and any significant alterations. Of the 113 buildings they seek to include, 67 are row houses, and 17 are tenements.

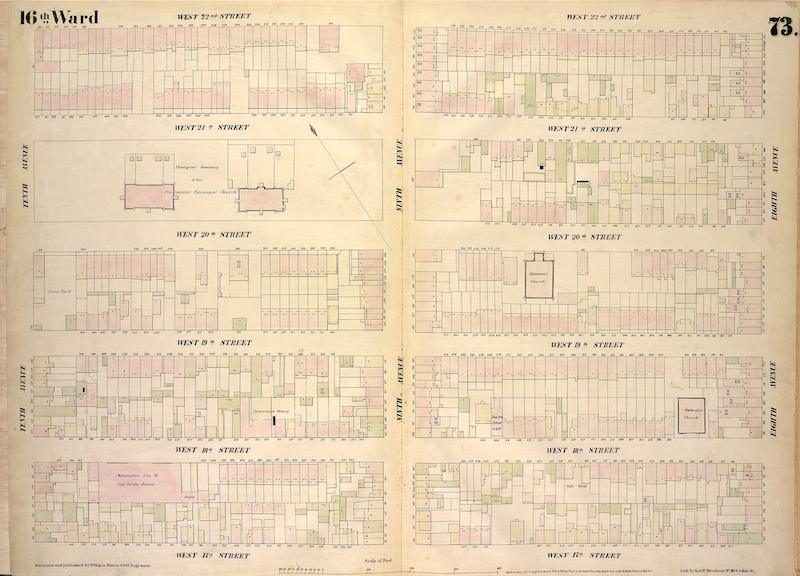

Holowka said they were able to infer some information by consulting maps of the City of New York, created between 1852 and 1854 by cartographer William Perris. Based on surveys conducted under directions of the City’s insurance companies, the seven-volume set was a precursor to later insurance and tax maps that would use color-coding to note if an individual building was constructed of timber or brick.

Some of these buildings, like the historic Cushman Row (406-418 W. 20th St. btw. 9th & 10th Aves.) and the General Theological Seminary (btw. W. 20th & 21st Sts., 9th to 10th Aves.) have been landmarked for half a century, since the Chelsea Historic District’s original designation of 1970. But there are many other historic rowhouses that Save Chelsea says merit preservation.

“On 19th Street, just outside of the Chelsea Historic District, are a few rowhouses that have lost their facades in the past years,” said Holowka. “The owner of side-by-side rowhouses at 345 and 347 West 19th Street destroyed their facades and destabilized the adjacent rowhouse to their west, number 349, so that its facade had to be removed as well. This triple loss of Federal-style rowhouses, likely pre-dating 1835, brought home the urgency of extending landmark protection to more of Chelsea’s historic buildings.”

As for the building at 345 W. 21st St., which did not make the cut at the time of the Chelsea Historic District’s original 1970 designation, Holowka says thinking has changed about the integrity and legacy of tenement buildings–making 345 as deserving of District designation as the Greek-Revival rowhouse next door at 347, which has always been part of the Chelsea Historic District.

“Now,” asserted Holowka, 345 is “a half-century older, and no less architecturally remarkable,” noting that a precedent-setting recognition of tenement structures can be seen “in the LPC’s 2016 designation of the Sullivan-Thompson Historic District [in SoHo], which is largely made up of tenements.”

And so as the argument in favor of District expansion advances, so too do the necessary mechanics demanded by the process. Save Chelsea will need to make computer printouts of the Property Profile or building application from a public access terminal at the DOB. Once they have the building date and architect, they may want to do further research at the New-York Historical Society and the New York Public Library, whose Map Division is a good source for early maps that can help date building development in an area.

This detective work will help form a profile of the neighborhood’s history, showing the important people and companies that resided there as Chelsea developed and grew.

“In order to qualify to present this kind of thing, you need to go into incredible detail about every building included in the new District or extension, and it’s intense,” said Pamela Wolff, a longtime champion of neighborhood beautification and preservation who currently serves as first vice president of Save Chelsea.

The project’s multi-year commitment from inception to research to advocacy to hopeful extension, said Wolff, requires “someone who’s detail-oriented, who knows what they’re doing, and has the time and heart for it, which is a tough order. I know David is more than capable of all of this, and I am so in admiration of his tenacity and devotion to the concept, and his willingness to be in the struggle.”

Because the NYC Landmarks Preservation Commission (LPC) prefers clear boundaries to their districts, Save Chelsea is also seeking to preserve more modern buildings that, when included in a historical district, should be looked at from a historical viewpoint. For example, the Church of the Guardian Angel (aka Parish of Guardian Angel/St. Columba, at 193 10th Ave. btw. W. 21st & 22nd Sts.).

“Guardian Angel Church was built in Sicilian Romanesque style that makes it look older than its 1930 construction date. Its brick and stone design fits well with nearby London Terrace, built about the same time,” said Holowka. “The church was built with funds provided by the New York Central Railroad as part of its construction of the High Line, which required demolition of the parish’s church two blocks north on 23rd Street, built only 20 years earlier. These costs were part of the $150 million—more than $2 billion today—spent on the High Line project. Because they were designed in concert, the High Line very narrowly bypasses the back of the church.”

They’ll also include some tenement buildings near 347 W. 21st St., where the dividing line currently sits. Holowka said some of those buildings are richly detailed. A common tenement feature, the carved Green Man face with horns and wavy hair, which can be seen on 303A W. 21st St., may have been meant to address immigrants’ superstitions about deflecting the evil eye.

History Surrounds Us in Chelsea |As Holowka continued his research, he began to notice the historical buildings one block eastward, from his residence–a group of six Greek-Revival rowhouses standing side-by-side, from 319 to 329 W. 19th St. The buildings originally matched. Although changes have been made to individual houses over time, the group retains the power of a unified ensemble. “What a shame,” remarked Holowka, “if any one of them were lost.”

The row of houses graces the street with 10-foot garden setbacks–a preferred planning feature of Clement Clarke Moore, who wrote Twas The Night Before Christmas. Moore inherited much of the still-rural estate once owned by his late grandfather, Major Thomas Clarke, who bought a Dutch farm and named it Chelsea after the Royal Chelsea Hospital, a retirement home for old soldiers in London. The name was a joke, with Clark laughing up his sleeve that his retirement home would be that of other soldiers now past their prime.

But when the City settled on a grid street system in 1811, Clark realized the property would be sliced into urban lots. So he leaned in, and put the lots up for sale, setting aside a plot of land for the General Theological Seminary, with the idea that it would be the new neighborhood’s anchor park.

In 1839, his friend Don Alonso Cushman built Cushman Row across the street from the General Theological Seminary, which was gratifying to his ideal of Chelsea as a genteel rowhouse neighborhood.

He also pointed to PS11 (321 W. 21st St. btw. 8th & 9th Aves.), designed by C. B. J. Snyder, Superintendent of School Buildings for the NYC Board of Education, and architect of nearly 20 NYC landmarks, including Erasmus Hall High School (Brooklyn) and the original Stuyvesant High School (Manhattan). “PS11’s ongoing restoration might be more authentic, ” said Holowka, “if the building were landmarked and work was overseen by the LPC.”

As Save Chelsea conducts this research process, City records should help them discern who the architects were and when the buildings were constructed, and any notable residents. The process is similar to what Save Chelsea board member Andrew Berman did successfully, in order to extend the 1969-designated Greenwich Village Historic District (twice, in 2006 and 2010), and bring about 2003’s creation of the Gansevoort Market Historic District.Holowka said they were grateful for the guidance from Berman, as well as from Simeon Bankoff, of NYC’s Historic Districts Council.

“There’s much great history and architecture in Chelsea outside the current bounds of the Chelsea Historic District which is being lost or could be lost without the Landmark protections other parts of the neighborhood enjoys. This includes early 19th century houses and early 20th century churches connected to the history and development of our city,” said Berman, Executive Director of The Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation (or Village Preservation, as per a recent shortening of the name). “Many historic districts designated decades ago failed to capture all the worthy history of their neighborhoods, or overlooked sites we would now consider significant or precious. Revisiting these boundaries is certainly something worth doing now.”

In doing this work, Save Chelsea will also need to individually photograph each building. In addition, they must continue to communicate with the community and remind them of their ongoing work to extend the historical district. They’ll talk to new residents, landowners, Manhattan Community Board 4 (CB4), and elected officials.

Support of Electeds and City Agencies | The work that Save Chelsea is doing has not gone unnoticed by elected officials, many of whom understand the value of historic districts and preserving these buildings.

Said NY State Senator Brad Hoylman, “I strongly support an expansion of the Chelsea Historic District. We recently lost three Federal-era row houses on West 19th Street—some of them close to 200 hundred years old—which means additional historic buildings could fall unless we take steps to protect them through the expansion of the historic district. I pledge to fight alongside Save Chelsea and preservationists to protect our history from being demolished.”

New York City Council Speaker Corey Johnson echoed this sentiment, noting that his neighborhood of Council District 3, “includes some of the most architecturally and historically important blocks in New York City. Unfortunately, many of these blocks are not included in the Chelsea Historic District. For years, I have stood with Save Chelsea, CB4 and residents in support of expanding this district so we may ensure this historic neighborhood is here for future generations to experience and enjoy.”

This bodes well for the project’s success. But Save Chelsea will also need to maintain an open dialogue with LPC, to discuss concerns and discoveries. Presenting a case for preservation through rock-solid research is important. It can take years to complete.

When all of the research and photography is done, Save Chelsea will then present their plan to CB4, which could submit an advisory letter to the LPC, in support of the extension.

It’s still too early to bring this proposal before CB4 for review. But Betty Mackintosh, co-chair of CB4’s Chelsea Land Use Committee, said that “once we get the proposal, we would bring it to the CLU—probably ask for a presentation of it at a CLU meeting, then discuss it. Perhaps we would vote and then bring a resolution to the full Board.”

Pamela Wolff, who currently serves as a public member of the CLU (alongside CB4 member Holowka), said she’d be part of the discussion when it reaches their committee, which is now dealing with historic projects, since that work fell to them after the Landmarks Committee was dissolved. Ironically, after years with very little activity, these sort of projects are now cropping up around Chelsea, including some that neighbors are not thrilled about, like the proposed nine-story commercial office in-fill at W. 14th St. and Ninth Ave.

Eventually, Save Chelsea will submit a formal application to the LPC for consideration of the proposed Chelsea Historic District Extension, using the LPC’s Request for Evaluation (RFE), a one-page form that requires the contact information for the group, location of the building or district to be evaluated, and information about its history, significance, and conditions. A basic report stating the case for preservation should be submitted, along with photographs of each building.

When a building becomes part of a historic district, noted Holowka, “Changes to them fall under the purview of the LPC.” Before any decisions are made, CB4 and the LPC must hold their own public meetings, at which they and members of the public can fully discuss the matter. Recommendations are then sent to the LPC in the form of a CB4 advisory letter. However, “The LPC can ignore CB4’s advice, and even deviate from its own norms in specific instances,” said Holowka, who noted that noted historic district status has proven useful in providing “important protections against the loss of historic buildings and features.

Designating an area as an Historical District is often financially beneficial for building owners, leading to higher property rates and a stronger community in general. The LPC has recently updated their Rowhouse Manual, a guide to help owners preserve and maintain their homes.

Presumably some owners will want to avoid oversight of alterations to their property by the LPC, or fear that designation may reduce the resale value of their property. This is short-sighted. A 2003 study by the NYC Independent Budget Office found that properties in historic districts increase in value at a greater rate than comparable ones outside districts.

Preserving a historic rowhouse means owners must work with LPC guidelines for exterior property alterations. This is a daunting prospect to real estate brokers or investors, who view this as a negative because it restricts what they can do and slows down approvals. But even financial analysts say property values in local historic districts appreciate faster than the market as a whole, meaning this move could benefit the community in the long run.

“There are definitely two sides to that argument,” said Wolff. “A lot of landlords will fight tooth and nail against it so they can do whatever they want with a building’s façade and extensions (what you can see from the street). But generally speaking, historic district designation increases property values over the long haul. If somebody owns a building that is already improved, that is now in a historic district, it will ultimately get a better price, because buyers know it’s not a home that could end up having two 20-story buildings constructed on either side of it.”

Wolff said if Save Chelsea is unsuccessful with their proposed Chelsea Historic District Extension, they will instead look toward preserving individual historic properties in the community by landmarking them through LPC.

Hopefully, it will not come to this. One wonders what Chelsea would look like now, had it not first been designated a historic district 50 years ago. The ability to protect the history of Chelsea only raises its desirability as a place to live.

Chelsea Community News is made possible with the help of our awesome advertisers, and the support of our readers. If you like what you see, please consider taking part in our GoFundMe campaign (click here). To make a direct donation, give feedback about the site, or send a Letter to The Editor via email, at scott@chelseacommunitynews.com.

Pingback: คลิปหลุด

Pingback: cc cvv shop

Pingback: free dumps

Pingback: nova88

Pingback: buy cz guns USA online

Pingback: ถาดกระดาษ

Pingback: Writemypapers.Org Writing Service Review

Pingback: relx

Pingback: Replica watches used

Pingback: white house market

Pingback: darkfail