BY MICHAEL MUSTO | I’ve always had a complex love/hate relationship with the art of attention-seeking. As a shy child, I always craved the spotlight, but since I was conditioned to feel unworthy of it, I got nervous about success and sometimes sabotaged my chances to seize it. My familiar pattern is that I’m dying to be center stage, then squirm once I get there and try to wiggle my way off, back into the sidelines.

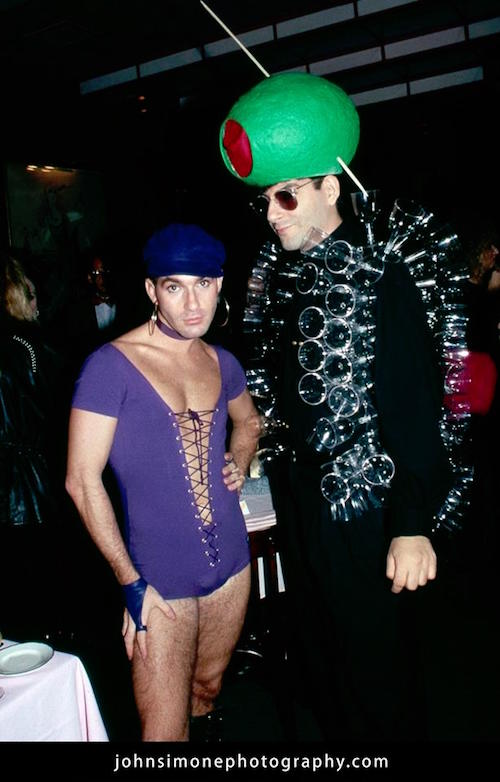

Jump ahead and I’m running through nightclubs with a large papier-mâché cocktail olive on my head, obviously pleading to be noticed, only to find that: (A) On the club scene, everyone is wearing a large papier-mâché cocktail olive on their head. (B) My wearing gowns and boas wasn’t exactly what you’d call career enhancing. I got noticed all right, but corporate America turned its back, admiring (while snickering) from afar. So while I was getting photographed, dressing up was another way to ensure that I could be comfortable with the level of attention I was getting. I was an alternative guy from an alternative weekly (the Village Voice), and that’s where I basically felt I belonged. Still, I was far from little Mikey, wilting in the corner—and all the focus-grabbing had a purpose apart from sheer ego-boosting.

As fellow columnist Cindy Adams once noted, “You wear crazy outfits to get more notice for your writing, don’t you?” So, one form of attention can beget another form, I learned while whipping up ensembles and puckering for the cameras. If it wrecked my career half the time, at least it enhanced it the other half.

Meanwhile, it complicates things that I have always covered people who are seeking attention themselves. They’ve always flattered me, acted out for me, and longed for a mention, while doing and saying naughty things in hopes of grabbing my focus, even for a negative writeup. (“There’s no such thing as bad press,” they always say—and I always repeat that back to them when they don’t like what I wrote.)

I’ve long been aware of the weirdness of being a journalist who’s playing the same game as my subjects, but I’m also not your typical writer; my columns have always been editorial, first-person romps where a lot of the rules go out the window, for better or for worse.

And craving attention can be a healthy way of celebrating yourself. It’s only when it’s taken to extremes that it masks a massive insecurity in search of a Band-Aid. My low point came in the ’80s, when a friend told me I was mentioned in a Trivial Pursuit question. I frantically bought the board game and, as I sat watching a movie at a screening, I covertly glanced at the question cards in the dark to find the one with my name, hoping no one would spot what I was doing. It was pathetic—especially when it turned out to be the wrong edition of the game.

People who go too far with this addiction are blatantly looking for validation because they’re trying to make up for not having been loved enough as a kid, blah blah blah. They hijack every situation and put themselves at the center of it, aggressively seeking love from strangers, which may be the very essence of show biz—except that there’s a profound difference between the Meryl Streeps and the Kardashians of the world, not to mention between the Alexandria Ocasio-Cortezes and Marjorie Taylor Greenes.

Some push for career achievement while others just push. At various times through the years, I’ve done both, and while I’ve immersed myself in journalism, nightlife, theater, and cabaret out of a true love of self-expression, part of this routine also involves looking for a family to accept me, an arena full of potential approbation. This pattern started way back in school, when I joined just about every activity there was (except for sports), anxious for my expertise to be noticed and used—and it was gratifying when it was. My hunger for acceptance was ravenous, though sometimes I’d nervously scuttle my chances so I didn’t go too far, somehow managing to make myself a features editor, not the main editor, of the school paper; a supporting player, not the star, in the school musical.

In the ’80s and ’90s, I would not only dress up, I’d have gigantic parties in nightclubs that were guaranteed to get publicity, and the press mentions were personally fueled by me, myself, and I. Other columnists were happy to get some inside dish that they knew was real—since I’m out there in the trenches—and I was delighted to make more of a name for myself, all done in an honest fashion. When I had publicists work to promote my books, I found that I did a way better job than they did of getting press for the project. The publicists were amazed at the media I drummed up, but basically, I was connected with the writers and editors out there and knew what would grab their attention and how to present that information, since I’m on the receiving end of all that myself. But it felt much more fulfilling when I got press without trying, like when Page Six picked up some of my items on their own and upped the story a notch. That reminded me that my work could resonate by itself and that the buddy system is more mellifluous than a one-man band.

And constantly pushing your name out there can be wearying. It’s important to believe in your “brand,” but it’s just as rewarding to sit back and realize that your work and your life generate their own success without trying. Once you stop striving so hard, you can relax and just be, confident in your accomplishments and your merit. By necessity, the COVID lockdown took away the chance for continued fabulousness—among other things—and so, a lot of us “press whores” went cold turkey on the whole thing and found deeper values. These days, I’m leaning more towards being Meryl than Khloe—but I’m not throwing out a single feather boa, mind you.

Michael Musto is a columnist, pop cultural and political pundit, NYC nightlife chronicler, author, and the go-to gossip responsible for the long-running (1984-2013) Village Voice column, “La Dolce Musto.” His work regularly appears on this website, as well as Queerty.com and thedailybeast.com. Follow Musto on Twitter, via @mikeymusto.

Chelsea Community News is made possible with the help of our awesome advertisers, and the support of our readers. If you like what you see, please consider taking part in our GoFundMe campaign (click here). To make a direct donation, give feedback, or send a Letter to the Editor, email scott@chelseacommunitynews.com.

Pingback: dark168

Pingback: bio altogel

Pingback: marbo 9000 puff

Pingback: look at this web-site

Pingback: พรมปูพื้นรถยนต์

Pingback: 2005 gtx seadoo

Pingback: Buy Liv.52 Oral Drops - Himalaya Online

Pingback: slot gacor

Pingback: namo333

Pingback: 다시보기 사이트

Pingback: Yoga

Pingback: เสื้อวิ่ง

Pingback: daftar togel singapore

Pingback: 웹툰 다시보기

Pingback: เว็บสล็อต

Pingback: enkele plooi gordijnen

Pingback: 20105 Homes for Sale

Pingback: buy Ecstasy on line united states , Canada , united kingdom , Europe , Australia

Pingback: Anavar Vorher Nachher

Pingback: furbabiesandrealbabies

Pingback: สล็อตเว็บตรงไม่มีขั้นต่ำ

Pingback: Buy DMT Vape Pen New South Wales

Pingback: liberty cap mushroom lookalikes uk

Pingback: This Site

Pingback: mushroom store online ybor

Pingback: 이천자연눈썹

Pingback: wow slot

Pingback: sbobet

Pingback: สล็อตวอเลท

Pingback: 호두코믹스

Pingback: check over here

Pingback: short gun

Pingback: best place to get a fake

Pingback: most expensive champagne bottle

Pingback: Ruger firearms FOR SALE