BY GUY KETTELHACK | The meaning of epochal events, as often as not made dysmorphic over time by social change and the scatterings of fate, almost always undergoes a metamorphosis.

After 52 years the insurrection which marked the Stonewall Uprising (not a rebellion, not a riot) of June 28-July 1, 1969 may seem to the growing majority of people today who either weren’t born until after that date or weren’t old enough to understand it, to be a kind of mythic tale—a myth uninformed by recent, well-meaning attempts to expand our understanding of sexual identities as veritably incalculable. But those who were aware of the uprising when it happened could feel in that contemptuously homophobic era the potential threat of its killing bite. An ad hoc posse of gay men, lesbians, and drag queens in and around the Stonewall Inn on Christopher Street rose up against the police who, as was their periodic wont, raided the bar because that’s what you did with gay bars back then.

Such regular occurrences, not entirely incidentally, had the veneer of justice about them—because like nearly all NYC gay bars, it was run by the Mafia. But mostly, the brute push in it was homophobia, the kind of easy hate thought to be a normal response to any, but especially this, Godforsaken brick and mortar repository of homosexual perversity.

It’s not too much to say that the world changed that day.

Its significance was given public form on June 28, 1970, with the first Pride March (then called the Christopher Street Liberation Day March, embarked upon with trepidation: Most expected they’d be excoriated verbally, or worse. But it turns out they weren’t. What began as about 200 people in the Village became thousands by the time marchers reached Central Park, its final destination.

New York City was ready for this. The world was, too. Indeed, the city and much of the world had already, through the mid to late 60s undergone a moral and political sea change: Viet Nam, the “sexual revolution,” the proliferation of psychedelic drugs, the deaths of two Kennedys, Martin Luther King Jr., and Malcolm X. All of this, and, again, an undisguised sexual revolution. (“The Pill” made sex democratic between heterosexual women and men.

Overnight, it seemed, great realms of morality had shifted. Our notions of gender were starting to soften. But there was also a different, more concerted power in the push for the liberation of whole ranges of human variety: African Americans, women, Latinos, Asians—and by 1969 and 1970, gay men and lesbians. I was born in 1951, which meant I was 18 in 1969, and although I was off to college in Vermont, I continually returned to New York City in that first stretch of time, and moved into it for keeps in 1975. The city always promised and delivered to me something brutally, gorgeously, alluringly alive.

At this stage (ages 16 through 23), my life amounted overall to an extraordinary if often harrowing thrill. The giant mass of my baby boomer generation (1946-1964) marked a new human condition, and therefore a very new moment in social history. Never had so many people rethought so completely and freely who they might be, could be, would be. This liberty to re-invent yourself was a very strange psychic condition. In the sway and the roll of it, you can’t always find your center of gravity, or your heart, or your mind.

Zoom 50 years later to the Pride March, by this time a global celebration, not least because it marked the 50-year anniversary of Stonewall. Then think back last year to the utter vacancy of 2020, the only year the Pride March did not take place. And think, if you will, of the potent tangles and cessations of life through the imposed prison of the pandemic, the arrival of so many mentally ill and emotionally troubled people ascending from the shuttered subway system and on to the streets, howling at the sky. And think, if I might ask you to think now, of my dear friend John-Fredrick Williams, who died back in March, not of COVID, but of a heart attack, physically deriving from his having been born with a weak heart. (Unthinkably, he was born with congestive heart failure.)

John-Fredrick evinced all of the conditions of life I have just touched on—from delicacy to uproar. There were times he was homeless, there were times he was a powerful political activist in Act Up and Occupy Wall Street, there were times he would sing in the streets with a dear, much-loved friend of his—he was very musical, and very brilliant. He wrote reams of poetry, he was as often as not to be seen walking around in a kind of flowered frock worn over, depending on how cold it was, jeans or pulled-up socks and hiking boots. His hair was always a surprise; usually long, and dyed in unsuspected colors. He had small, intense eyes—indeed a power of intensity I don’t think I’ve seen in anyone else.

John-Fredrick and I met through the AOL chat rooms, sort of zapping odd clever strange phrases at each other, afraid to meet. But eventually we did meet. And we managed a kind of sex, rough and sweet and made up on the spot. We never—and I wonder generally if John-Frederick with anyone quite ever—found a completely habitable space to share. But he may have come somewhat closer to that with me than with most. I don’t know. Like Quentin Crisp (whom I worked with as literary agent), his friends were met mostly one-on-one. And I suspect he was marvelously attuned to each of those friends, when they didn’t piss the hell out of him (which was frequently).

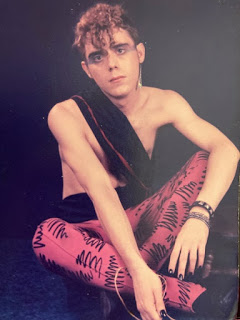

He was no stranger to pleasures and pains of extreme varieties. He felt very close to me. He paid a tight attention to my poetry and my singing and my writing and my art. He was one of those people who love with such an utter completeness that you truly don’t know how to respond—except to accept it. He got into you like a serum; you would be affected by him forever. The bracelet you see me wearing here is one he gave me. I don’t know its provenance. I’m not given to wearing jewelry. But I suspect I’ll wear this for the rest of my life.

What does John-Fredrick have to do with this history of gay liberation? He is central to it. He IS it. He lived a kind of aimed and passionate and irresponsible and deeply affectionate life. He was the human being in some ways we all ought to have looked up to for guidance. But he’s gone now. And there are few people, I think, who will remember him, beyond the handful who, like me, couldn’t bear to forget him. He has no biological family left. In this way, dare I say, he is us. He is every person who claims membership in our community, and he is also every person who belongs to the tribe of humankind. His is a spirit so tremblingly, organically constituted that if you could make real contact with him, you would know so very much more about being alive.

Few of us will be remembered at all, let alone in such a manner. And those who are remembered will, in time, fade away as well. And still, every one of us harbors and nurtures a very specific miracle. I think that’s what John-Fredrick would want me to convey as his message: Suck dick, fuck butt, kiss ass, laugh like a maniac, cry out of love, rail out of hate, be the whole business of you, tenderly, roughly, and share it at least once with someone else. He shared himself with me. And some very lucky others. And he remains for me perhaps the most striking example of the Believably Liberated Gay Homo Sapiens, which is to say the Freest Human Spirit, the incarnate goal, I think probably exactly as Christ was and was meant to have been, of Divinity become mud and ash, a frail detritus of life, as delicate a breath of nothing at the end as he was a clarion call to singing at the top of his lungs at the beginning.

Celebrate this time in June with someone like him in mind, and know that the liberation of Eros sparked by Stonewall stoked John Frederick and countless others to live the next 52 years in a state of unapologetic authenticity that made HIV/AIDS activism effective, ensured that Marriage Equality would become the law of the land, and today allows for an ever-broadening umbrella of respect and recognition for forms of gender expression and self-identity that has always been with us, but only now has a name that demands to be spoken. So when June comes around and talk turns to Stonewall, I’m more aware than ever that the history I lived through will be seen differently through the lens of each new generation—which will have their own opinion on how many colors a rainbow flag should have or how many letters it takes to abbreviate our community.

All of this would come to pass, I am sure, if there were no Stonewall. But there was—and one hot night in the summer of 1969, the right mix of combustible materials combined to create a whole new formula. Not least may have been Judy Garland exiting the planet when she did. Her funeral occurred a day before the Stonewall uprising, which although it’s since been persuasively discredited as a trigger, still may have tipped the balance a little. Hard not to believe, anyway, she wouldn’t have greatly approved of the change.

Had she somehow known from the other side that that her funeral was part of what made it happen, she’d surely have laughed long, loud, and proud.

Guy Kettelhack is the author and co-author of over 25 nonfiction books, including several on gay topics: e.g., “Dancing Around the Volcano,” “Easing the Ache,” and “The Wit & Wisdom of Quentin Crisp,” and “Vastly More Than That.” He fled the Long Island suburbs where he was born and grew up, and then climbed up and four years later out of the mountains of Vermont after a requisite sojourn at Middlebury College, to make a life in New York City—which he always knew would be, and has proven over 50 years to remain, the city of his heart. You see him here displaying the aforementioned inscrutable bracelet John-Frederick Williams gave him.

Chelsea Community News is made possible with the help of our awesome advertisers, and the support of our readers. If you like what you see, please consider taking part in our GoFundMe campaign (click here). To make a direct donation, give feedback, or send a Letter to the Editor, email scott@chelseacommunitynews.com.

You must be logged in to post a comment Login