BY WINNIE McCROY | When the pandemic shut down nightlife, filmmaker friends Elina Street and Erica Rose spent their evenings walking and talking, reminiscing about the things they enjoyed in the “before” times. Recalling a last drink shared at Brooklyn lesbian bar Ginger’s, the two began realized that even before the pandemic, the treasured dyke bars they took for granted had largely closed down. Quarantine shifted their perspective and their priorities, and they became determined to save those left.

“We are part of the community, and we didn’t even know the numbers were so low,” said Street in a recent interview. “It was time to make something meaningful to help the community.”

So, Street and Rose partnered up with Jägermeister’s #SAVETHENIGHT campaign, which Street called “a sponsor who’s not just supporting our community for [Pride] month, but throughout the year.” Using mostly archival footage from the likes of the Lesbian Herstory Archives, they created their Lesbian Bar Project fundraising campaign and a 2020 PSA.

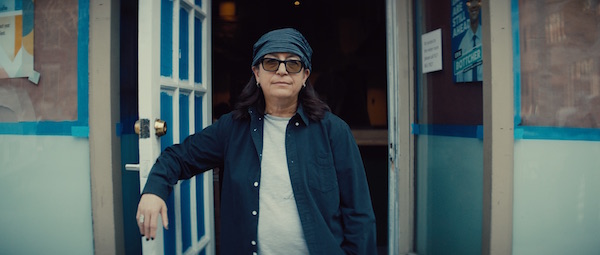

They wrote a script and enticed Orange Is the New Black star Lea DeLaria to become their narrator and later, the executive producer of the project. “I remember the first time I walked into a lesbian bar, there was this feeling… this is us,” DeLaria says in the PSA.

“Who wouldn’t want to partner up with such a landmark icon of our community?” Street said pointedly.

At the time, the filmmakers had identified only 15 remaining lesbian bars in the U.S.—a far cry from the 200-odd dyke bars that existed in the 1980s. The PSA raised more than $117,000 to divide among these bars and help keep them open and operating.

“I feel great about what we’re doing here; the conversation we’ve been having is a joy to my pea-picking, dago, greaseball heart,” said DeLaria. “But more than just the money is the awareness, the raising consciousness of these venues and the fight to keep these places open.”

DeLaria said it is a far cry from her own beginnings as a lesbian comedian in the 1980s, when queers were pariahs in the era of AIDS. She toured U.S. and Canadian lesbian bars doing stand-up, and is not sure her career would be where it is today without that early support. She’s dedicated to ensuring these places stay open for the next generation.

“When we launched it last fall, we didn’t expect the outpouring of donations to be so high,” said Street. “It was an incredible response. A few more bars revealed themselves, and the number rose from 15 to 21. The first iteration went so well, Jägermeister wanted to do a more in-depth piece.”

As the Lesbian Bar Project gained publicity, people began to discuss why these bars had closed. The primary reasons were gentrification, assimilation into the larger heterosexual community, and income disparity hitting women-owned businesses harder.

DeLaria told Chelsea Community News that because women don’t earn as much as men, they aren’t as readily able to afford rising bar rents—or even to patronize lesbian bars as often. Society has also changed, allowing gays to feel comfortable in many bars. But she also noted the strain of internalized homophobia keeping women away, saying, “As feminists we spend a lot of time talking about supporting women-owned businesses, yet we won’t go to a dyke bar.”

“In the rainbow alphabet, the ‘L’ is more downtrodden by our own community than any other letter. Even our young dykes are taught that we’re less-than,” said DeLaria. “They say they’d rather dance with the boys at the gay bar. Why don’t they want to dance with the lesbians at the dyke bar? It’s internalized homophobia that makes you feel that way, reinforced by heterosexual society.”

“There was also a big shift to the online culture,” said Street. “People were able to go online to set a meeting place, and that place was not necessarily going to be in a brick-and-mortar space catered to them. But it’s so important to have a meeting place for a marginalized community. Erica and I came into our authentic selves in bars like Cubbyhole, where as soon as we walked in, we met incredible women who became our mentors, friends, and future partners. I want younger generations to know that real memories are not created in front of a screen, but within those walls of your community.”

So, with some funding from Jägermeister, Street and Rose hit the road, filming documentary segments at Washington, D.C.’s As You Are Bar. They traveled to Mobile, Alabama to interview Sheila and Rachel Smallman, the lesbian women of color who recently opened Herz, who told them, “If we don’t fight for our people, who will?” The filmmakers also spoke with New York bar owners Lisa Cannistraci of Henrietta Hudson and Lisa Menichino of Cubbyhole, the bar Rose said, “knew I was gay even before I did.” DeLaria is also a huge fan of Cubbyhole, calling it, “my chosen family, the greatest lesbian bar in the world.”

On June 3, Street, Rose and DeLaria released the online world premiere of their 20-minute documentary short, The Lesbian Bar Project. Timed to Pride, the film celebrates the history of dyke bars, both those that remain open—like Oklahoma’s three dyke bars: Frankie’s, Alibi’s, and Yellow Brick Road—to those long-shuttered, like New York City’s infamous Bonnie & Clyde’s. They hope that the film will help raise an additional $200,000 for these bars.

“I’m hoping we can reach this goal by Pride. I’d like to think we can do anything if we put our heads, hearts, and minds together,” said DeLaria. “When I came out, I spent nights in jail for being gay. Did I think it would change in my lifetime so gay people could get married, or that we’d have an openly gay Cabinet member? Hell no! So, can we do this by the end of the month? Hell yes! But everyone needs to donate to help keep dyke bars open.”

Said Lisa Cannistraci, co-owner of Henrietta Hudson, “The money of course was very helpful, but I think the visibility part of it woke up people who didn’t previously support these spaces.” She’s seen many New York City lesbian bars open and close over the decades, and believes she survived by not trying to emulate anyone else, but instead focusing on her clientele and making changes when it was time—about every seven years or so—to cater to the needs of the evolving community. Henrietta Hudson has just seen its most recent renovation, transforming it from a dance bar with pool tables to a classy lounge, “like something on the Italian Riviera,” said Cannistraci. “I just focused on making it all about the girls, took a leap of faith, and it’s really working out.”

The documentary allows lesbian bar owners and community members to express, in their own words, what these spaces mean to them. Again and again, the same descriptor is employed: lesbians see these bars as their de facto community centers, the places where they can come together with their chosen families to celebrate community and history. The experience made Street and Rose eager to film an episodic Lesbian Bar Project, visiting every bar on the list.

“There is no place more comfortable for a dyke than a dyke bar,” said DeLaria. “In my generation, that’s all we had, and I don’t think these young dykes understand. We couldn’t go to the local straight place; in the ‘60s and ‘70s, some places wouldn’t even serve you a drink if you were gay.”

“The fact that we fought so hard to get these spaces; this was provided for you, and now you need to support this,” she continued. “Because the pendulum of history swings back—just look at what happened with Trump and his cronies who are still doing everything in their power to shut us down. We need to support these safe spaces, because when I walk into a dyke bar, I feel the weight of the world lift off my shoulders. No one will call me a dyke (in a bad way), or ask if I’m a man, or threaten to hurt me. I can sit down and have a beer and a shot, talk to my friends and maybe even finger a girl in the corner.”

These days, the gay community has cast a wider net, welcoming the entire LGBTQIA+ diaspora into the mix. The lesbian bars below welcome all members of our community. Said Cannistraci, “Henrietta’s pivoted from a lesbian bar in the ‘90s to a lesbian-centric bar in the early 2000s. Now we call ourselves a queer human bar, built by lesbians.”

“The spaces have changed throughout the years, and so has the language,” said Street. “All of these bars are not only for lesbians, but for all the LGBTQ community. Back in the day, people who went to lesbian bars weren’t just lesbian, they were also trans or non-binary, but now we have the language to define exactly who we are.”

The Lesbian Bar Project is dedicated to creating space for people of marginalized genders, and be inclusive of all individuals in our community. As they note on their website, these bars are disappearing at a staggering rate, and we cannot afford to lose more of these vital establishments to the fallout of COVID-19.

Here’s a List of the 21 Bars:

A League of Her Own — Washington, D.C.

Babes of Carytown — Richmond, VA

Henrietta Hudson — Manhattan, NY

My Sister’s Room MSR — Atlanta, GA

The Backdoor — Bloomington, IN

The Lipstick Lounge — Nashville, TN

Walker’s Pint —- Milwaukee, WI

Wildside West — San Francisco, CA

Yellow Brick Road Pub — Tulsa, OK

*Some of the bars listed closed before they started the campaign. Others, like Ginger’s in Brooklyn, have yet to reopen. Sue Ellen’s of Dallas, TX, and Wildside West of San Francisco, CA have graciously opted out of the Donation Pool to allow for more support of other bars.

Chelsea Community News is made possible with the help of our awesome advertisers, and the support of our readers. If you like what you see, please consider taking part in our GoFundMe campaign (click here). To make a direct donation, give feedback, or send a Letter to the Editor, email scott@chelseacommunitynews.com.

You must be logged in to post a comment Login