BY EILEEN STUKANE | His paintings of city rooftops and life within urban windows are so familiar, it’s surprising that Edward Hopper’s New York is the first museum exhibition addressing the artist’s relationship to New York City. The Whitney Museum of American Art’s 2015 move from its uptown East Side home to 99 Gansevoort Street in the Meatpacking District brought it to within a 15-minute walk of Hopper’s studio/home on Washington Square North.

Although the Whitney, which holds over 3,100 works by Hopper, has had a number of Hopper exhibits (the last one in 2013 was devoted to his drawings), “That the Whitney is downtown sparked the idea of thinking about Edward Hopper through the New York lens,” says Kim Conaty, the Steven and Ann Ames Curator of Drawings and Prints at the Whitney, and curator of the exhibition which opened October 19 and is on view until March 5, 2023.

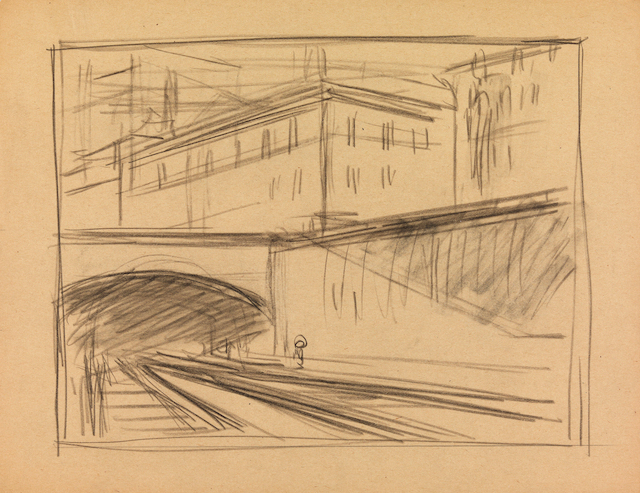

Hopper, born in 1882 in Nyack, New York, began trips into the city for art classes right after high school. Entering the exhibition feels like entering the city from a height. A dropped-from-the-ceiling screen allows a black and -white 1916 film projection to take visitors on one of the elevated trains that once were ubiquitous in Manhattan. Hopper took these trains. He had a penchant for painting views as seen from above. On a nearby wall is his New York City Pavements (1924) oil painting looking down on the entrance to a greystone apartment building reminiscent of many that can still be seen today in Chelsea and Greenwich Village.

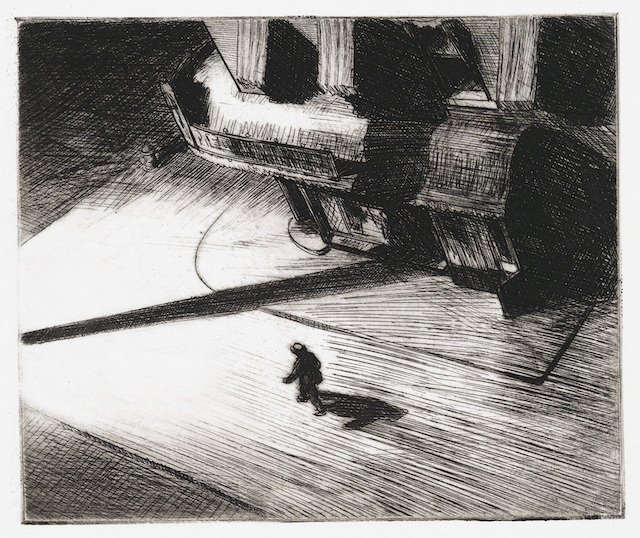

Edward Hopper’s New York is designed to feel like a stroll through time, much as one might walk the city streets—but here, you’re among 200 works of Hopper’s. The exhibition is organized into eight sections, with four being pastel-colored rooms Conaty describes as “pavilions for deep dives into focused topics [The City In Print; Washington Square; Theater; Sketching New York]. The concept was to create a sense of exploration rather than a scripted path, to forge connections between Hopper’s work across thematics and across decades. Also hopefully to emulate the feeling of walking through the city, peering around a corner, stepping inside an interior and emerging once again.”

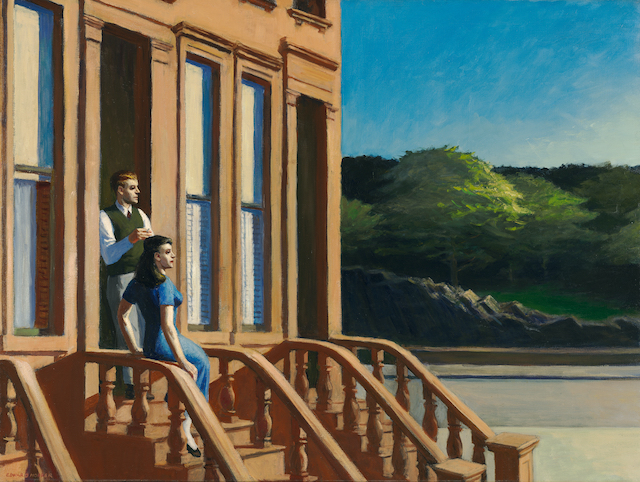

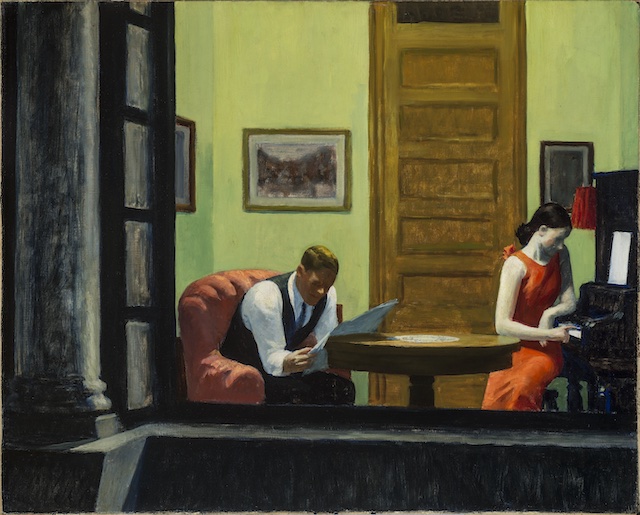

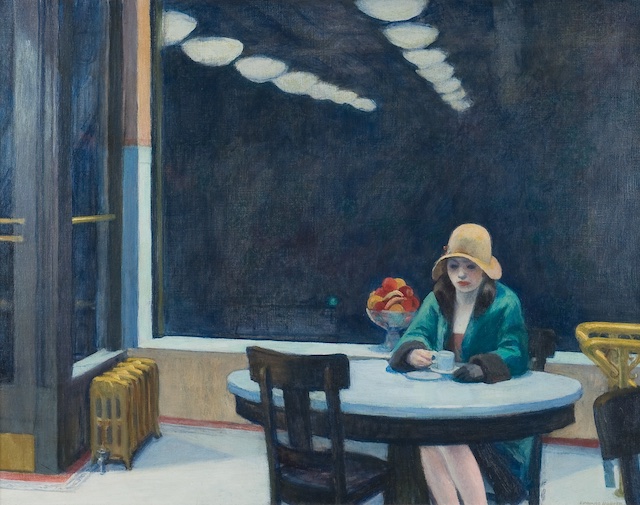

This succeeds because Hopper’s work is relatable and soulful at every turn, throughout each decade of his life, whether he has captured the solitude in a venue that should be people-filled, as in his oil painting New York Movie (1932) or the remoteness of a couple, a man and a woman, on a stoop, amid the earthly colors, in Sunlight on Brownstones (1956). Looking at his works is a lesson in seeing importance in the ordinary.

In 1908, Hopper moved to Manhattan, living first on West 14th Street, then on East 59th Street, finally settling in 1913 in a walk-up rental apartment on Washington Square North, where he and his wife Josephine Nivison Hopper, also an artist, lived and worked together until his death in 1967. The Washington Square pavilion includes a short black and white film (produced by Voice of America in 1965) of Edward and Jo Hopper, both working at their easels in their stunningly small studio with a potbelly stove. Hopper has described New York as “the American city that I know best and like most.” During COVID lockdown when the streets were as empty as Early Sunday Morning (1930), a work Hopper himself identified as Seventh Avenue Shops, and there was no traffic on the Manhattan Bridge Entrance (1926), the timelessness of his beloved early 20th century New York became apparent. (Unfortunately, the iconic New York diner and deserted streets of Hopper’s Nighthawks(1942) has remained at its home at The Art Institute of Chicago.)

The dislike Hopper had for the emerging “verticality” of the city, as Conaty explains, is shown by the fact that he painted the horizontal Early Sunday Morning in 1930, the same year the Chrysler Building was completed. Like so many of today’s New Yorkers, he fought real estate development and gentrification in his neighborhood. In the exhibition are letters Hopper wrote to Robert Moses in his attempt to save Washington Square from the ever-encroaching New York University. Moses’ reply is also included in the exhibition. Much of the Hoppers’ personal ephemera is on display for the first time.

Not only do Hopper’s early sketches, prints, illustrations, and later paintings show his connection to the city, but what is also striking are the notebooks and ledgers he and his wife used to record the works. These are in glass vitrines along with diaries, correspondences, photographs, even theater ticket stubs, all from the Sanborn Hopper Archive recently acquired by the Whitney. (Note: This Archive was held by Reverend Arthayer R. Sanborn, a Baptist minister who reportedly cared for Hopper’s sister in Nyack and later, Hopper’s wife Josephine. Sanborn came to own the contents of the Nyack house and the New York City studio. He died in 2007.)

“We all know that New York has many histories beneath its surface,” says Kim Conaty, “We see buildings come and go every day, but we also see buildings that stay. As I’m walking through the neighborhood something catches my eye, an old-fashioned architectural flourish, and I realize, this is the type of building that Hopper was looking at. It may be right up next to a modern glass-front building, but it’s still here. Hopper is an interesting reminder to notice our city around us.” More often than not, many of us are looking at cellphones when we’re walking, answering texts, sending emails. “We increasingly tune out as we tune into a device in our hand or a headphone in our ear, or we have masks on,” says Conaty, “Now, I think about what I’m missing, that storefront window, or these moments that hover over an incredible city. I like the idea that you might be reminded from a show like this to notice what’s around you, all the curiosities.”

Fittingly, Edward Hopper’s New York finds its way to the Whitney’s eastern wall of windows, and suddenly his City Roofs (1932) does not seem consigned to the past. The framed view of rooftops from the Whitney’s windows could be a Hopper painting, created during any given decade when the City was his.

Edward Hopper’s New York is on view through March 5, 2023.

The Whitney Museum of American Art is located at 99 Gansevoort St. (btw. Washington & West Sts.). Public Hours: Mon., Wed.,Thurs., 10:30am–6pm; Fri., 10:30am–10pm; Sat./Sun., 11am–6pm. Closed Tuesday. Member-only hours, Sat./Sun., 10:30–11am.

General admission is $25, adults; $18 for students, seniors, visitors with disabilities (Disability tix includes free admission for one care partner). Visitors 18 years and under and Whitney members: FREE. Admission is pay-what-you-wish on Fridays, 7–10pm. Tickets are limited and advance reservations are strongly recommended. Reserve tickets. COVID-19 vaccination and face coverings are not required but strongly recommended. The Whitney encourages “all visitors to wear face coverings that cover the nose and mouth throughout their visit.” Questions? Call 212-570-3600 or email info@whitney.org.

Chelsea Community News is made possible with the help of our awesome advertisers, and the support of our readers. If you like what you see, please consider taking part in our GoFundMe campaign (click here). To make a direct donation, give feedback, or send a Letter to the Editor, email scott@chelseacommunitynews.com.

Pingback: Hopper Opportunity Invites You & Your Story to ‘Step Into’ a Trio of 3D Paintings - Chelsea Community News

Pingback: Our Arts Writers Garner First Place Award, in NYPA’s Better Newspaper Contest - Chelsea Community News