BY TRAV S.D. | In honor of Pride Month, we will be featuring one article per week on a different classic performer, one for each category: L, G, B, T, and Q! With only five weeks in June, that’s our limit. Check back with us next year, as our series picks up with “+” I, A, and beyond. . .

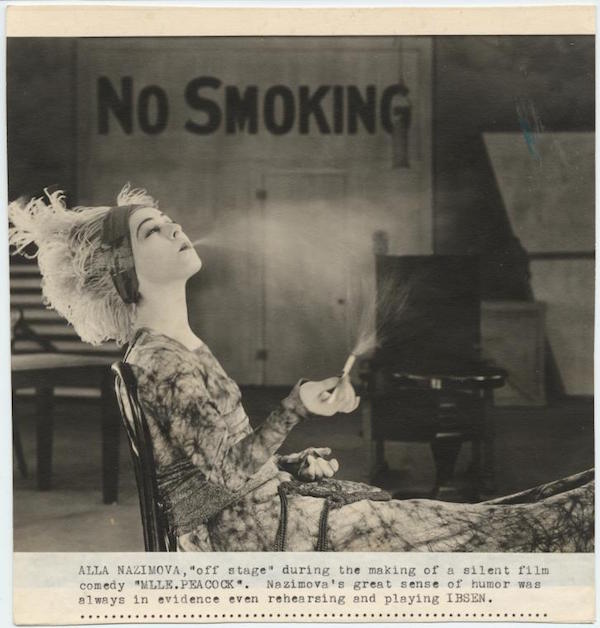

Starting off with our “L”—the great stage and screen actress Alla Nazimova (Marem-Ides Leventon, 1879-1945). Nazimova is credited with being the person who coined the term “sewing circle” for a group of lesbian friends.

Nazimova was actually bi, FYI–she had some relationships (and one marriage) with men. But she is almost universally regarded as a lesbian icon and pioneer. Her lovers included actress Glesca Marshall (her longtime companion), designer Natacha Rambova (who was also married to Valentino), Broadway star Eva La Galliene, film director Dorothy Arzner, writer Mercedes de Acosta, painter Bridget Bate Tichenor, and Oscar Wilde’s niece, Dolly.

One of the great actresses of the early 20th century, Nazimova was also one of the stage’s great sensationalists. She was born Mariam Edez Adelaida “Alla” Leventon in Yalta. As a child she had studied the violin, but fear of her stern father prevented her from formal dramatic study until the age of 17. She was accepted to Vladimir Nemirovich-Danchenko’s Philharmonic School in Moscow, which merged with Stanislawski’s newborn Moscow Art Theatre in 1898.

She struggled on in minor roles and as a stage manager with the theatre for a few years, and then split off to act with the Kostroma stock company. While there, she met Pavel Orlenev, a friend of Chekhov and Gorky. The two became collaborators and lovers. From touring the Russian provinces, in 1904 they went on to success in Berlin and London. In 1905, they were a hit in New York, where the Shuberts were so impressed, they offered to produce her if she would stay in the U.S. and learn English. She did.

Her 1906 performance as Hedda Gabler was such a hit that Nazimova went on to star in most of Ibsen’s major plays over the next few years. She almost always did “important” realistic plays, usually with progressive political themes. A gorgeous woman, with enormous eyes and a sensuous mouth, she reinforced the sensationalism of her feminist forays by giving them sex appeal. This is what made her a hit on the vaudeville as well.

In 1914, she debuted a one-act at the Palace Theatre called An Unknown Woman, which pleaded for more sensible divorce laws. The management cancelled the act at the urging of a Roman Catholic clergyman, although Nazimova was paid in full for her services. In 1915, she returned with the pacifist playlet War Brides, which was especially timely given the conflict overseas. This turn was such a hit she toured the Orpheum Circuit with it, and then turned it into a 1916 movie. The film version was a major success, resulting in Metro offering her a five-year, $13,000 a week contract in 1917—a deal better than even Mary Pickford’s.

For the next several years, she was a major movie star and the mansion she built “The Garden of Alla,” one of the centers of the Hollywood social scene. Her contract gave her total creative control, and unfortunately, as time went on her use of it alienated both critics and audiences. Her exotic sexuality was often exploited, which critics found “lurid” and “preposterous.” She lost audiences by indulging her artistic impulses. She began to allow free reign to experimental set designer Rambova (whose husband was Rudolph Valentino, who was Nazimova’s co-star in the 1921 film Camille).

Though Camille was a success, Metro started becoming uncomfortable with all of this art, and cut Nazimova loose. She produced two films on her own in 1922—A Doll’s House and Salome—which continued with the stylized sets and acting. They tanked at the box office, unfortunately, and Nazimova was to play only small roles in Hollywood thereafter.

It is perhaps for this reason that she returned to the Palace for several vaudeville engagements through the 1920s. One of the playlets she introduced was a feminist drama called India. Major theatre roles of her late career included Christine in the original production of Eugene O’Neill’s Mourning Becomes Electra (1931), O-lan in Pearl Buck’s The Good Earth (1932), and the leads in major revivals of Ghosts and Hedda Gabler, which she directed in 1935 and 1936, respectively. She died in 1945.

Chelsea Community News is made possible with the help of our awesome advertisers, and the support of our readers. If you like what you see, please consider taking part in our GoFundMe campaign (click here). To make a direct donation, give feedback, or send a Letter to the Editor, email scott@chelseacommunitynews.com.

Pingback: ทดลองเล่นสล็อต pg

Pingback: แทงมวยออนไลน์

Pingback: บาคาร่าเกาหลี

Pingback: bangkok tattoo

Pingback: ไม้พื้น

Pingback: jaxx download

Pingback: fenix168

Pingback: เช่าจอLED

Pingback: สรุป สมาชิก ibc-ibcthai มาแทงบอลกับ LSM99 แทนดีหรือไม่

Pingback: saคาสิโน

Pingback: SWS Marketing

Pingback: โบท็อกราคา

Pingback: Donald

Pingback: ยกตัวอย่างของการเลือก แทงบอล 4 ตังค์

Pingback: https://hitclub.blue

Pingback: safe fortnite cheats

Pingback: หวยดวงดี

Pingback: psilocybin microdosing kits Europe

Pingback: diyala uni

Pingback: เสริมหน้าอก พัทยา

Pingback: x4rich

Pingback: ข้อดี ของ LSM99 เว็บหวยจ่ายไว

Pingback: scooter in vegas

Pingback: ufabtb

Pingback: Real Time Pain Relief

Pingback: บาคาร่าออนไลน์

Pingback: penis prosthetic big penis big prosthetic big dildo erect penis prosthetic

Pingback: click this over here now

Pingback: Best Psychedelic Store Brisbane

Pingback: additional resources

Pingback: sbo

Pingback: can you buy psilocybin online

Pingback: read the article

Pingback: dumps with cvv

Pingback: Text inmate

Pingback: FUL

Pingback: dumps 101 shop

Pingback: Bildemontering Partille

Pingback: Onion

Pingback: kardinal stick