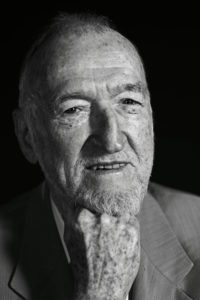

BY GERALD BUSBY | Collaborating with young gay writers, filmmakers, and choreographers has been a major stimulus to my creative life as an 83-year-old composer. The same could be said of my association with young straight artists as well, though I’ve felt a special satisfaction, a completion really, in sharing my history as a gay artist with other gay artists who are 40 to 60 years younger than I.

At the beginning of my career, I accepted the conventional wisdom that the best environment in which to create was one of comfortable isolation. My mentor, the composer/critic Virgil Thomson, who got me an apartment at the Chelsea Hotel in 1977, suggested that I spend time at Yaddo and the MacDowell Colony, two artist colonies that are idyllic retreats from the distractions of day-to-day living. I wrote lots of music at those places and met many other artists, but I gradually realized that creativity, at least as far as I was concerned, depended more on social interaction than isolation. This has become increasingly true as I’ve gotten older.

John MacDermott, a friend for many years, contacted me not long ago to say he was engaged to a bright young composer/performer who wanted to meet me. Their name was Jake Bellissimo, a 23-year-old transgender musician/performer who lives most of the year in Berlin, makes albums, and tours extensively in the U.S. and Europe. John took me to hear Jake perform at a cabaret in Brooklyn, and I was impressed with the intimate charm and invention of the songs.

There was no amplification, and Jake’s accompaniment was various musical instruments, some of them toys. Many of the songs told stories about being transgender, coming out to parents, and becoming engaged to a man 34 years older. Jake’s emotional singing ranged from whispers in your ear to sharply penetrating exclamations in full voice. Jake’s voice was steady and perfectly in tune, a quality perhaps acquired as a viola major at Eastman.

When Jake sent me a poem and asked me to set it to music, I was honored and delighted to do so. I asked them if they could sing and play the viola at the same time. They said yes, so I began a duet for one person. Jake liked my musical ideas and executed them perfectly, but there were textural problems when I wrote double stops (two notes at once) for the viola. Jake suggested pizzicato instead of double stops, and that worked perfectly. It was a real collaboration, and done completely online. It’s called The Budding of a Rose, Jake will record the song and take it on tour.

My collaborations with David Kagan, a young filmmaker, were exactly opposite the way I worked with Jake Belissimmo. I met David and his husband, Gabriel Beck, at a cabaret performance of my music by Adam Tendler and Brandon Snook. I invited them for tea at my place at the Chelsea Hotel. David gave me a short film called Do Not Feed Horses that he had created from footage he shot during his travels to South Korea and Ghana. He appeared in these distinctly foreign and exotic environments dressed in a black suit with a white shirt and a black tie. All his films, I came to discover, were self-portraits, and the ways he found to present himself were daring and surreal. He was an adventurer, and I liked that.

When he gave me his film to score, I was happy that he said nothing about what he expected the music to sound like, or exactly where he wanted each cue to be. I preferred to set David’s visual images to music the same way I set words and phrases in a poem, without any discussion with the author about meaning or intention. Several times, I’ve set poems to music without even reading through it. I decided I liked them after reading just the first line. I wanted each word, as I read it for the first time, to guide me to the right note.

When I finished composing the score for Do Not Feed Horses, I sent it to him with the understanding that he could edit my music any way he wished to make it fit as he liked. This reciprocal method of minimal discussion of expectations, David’s or mine, worked for us. It was my version of what I experienced when I wrote music for the 1977 Robert Altman film 3 Women. He allowed me, with no directions, to create any sounds I wished, to accompany his images. I never felt so empowered in my life. His trusting me with no considerations taught me to trust myself the same way. That method of working, I think, was the purest form of his genius. It epitomized inspiration.

Another film David and I did together, Regarded as a Hole, was shot at the Chelsea Hotel, where I live, during the renovation of apartments across the hall from me. David directed every detail, and we both appeared as ghosts/characters in the film. He read an original poem, Regarded as a Hole, and I sat wordlessly listening to every word. One scene was shot in the gutted interior of an apartment where Mildred Baker, a close friend, had lived for more than 40 years. I had often visited her and had dinner exactly where I sat to be hearing David intone his words. I felt like a ghost, and that made itself evident in the music I wrote for the film.

Eryc Taylor, the creator of modern dances that have a distinctive sensuality, was a choreographer whose work I first encountered through a mutual friend, the painter Mark Beard, a prodigious producer of romantic homoerotic art. Mark was an admirer and supporter of Eryc’s and had more than once asked Eryc to model for him. Dancers and painters, especially gay ones, share a rigorous and meticulous fascination with the physiology of young male bodies.

I contacted Eryc through Facebook and asked him to come to my place at the Chelsea Hotel for tea and tunes. I have studio monitor speakers connected to my computer so I can give listeners a reasonably accurate sense of my music. Eryc seemed to like it, and we became fast friends. He already knew my music for Paul Taylor’s Runes and he had studied at the University of the Arts in Philadelphia with Ruth Andrien, an original cast member of Runes. I also visited Eryc’s studio where he rehearses with his company and saw how organized he was and how responsive his dancers were to his choreography.

Eryc’s responses to my music were primarily intuitive. He responded to the spirit and rhythm of my music, not its form, something I remembered being true of Paul Taylor, when Runes was being created. Nevertheless, I couldn’t resist trying to interest Eryc in the music of Bach and Mozart, saying, “If I’m going to be Stravinsky to your Balanchine, you’ve got to know the greatest composers who ever lived.”

I wrote a suite called Dances on Wood, for piano and percussion ensemble. Each of the four movements was named for a different kind of wood. The piece was premiered by Eryc Taylor Dance at their annual New York season in the Martha Graham Studio. I couldn’t have been happier with the result. Eryc’s talent and good nature had totally transcended all my academic considerations about musical sophistication. He didn’t really want to be Balanchine. He was at his best being himself, and I was fortunate to work with him.

Chelsea Community News is made possible with the help of our awesome advertisers, and the support of our readers. If you like what you see, please consider taking part in our GoFundMe campaign (click here). To make a direct donation and/or send feedback about the site, send an email to Scott@chelseacommunitynews.com.

Pingback: tải no789

Pingback: บาคาร่าเกาหลี

Pingback: pgslot

Pingback: Dark Net Links

Pingback: video chat

Pingback: Sagames ดีอย่างไร มีจุดเด่นอะไรบ้าง

Pingback: virtual office for rent

Pingback: ufa191

Pingback: 789 club

Pingback: ผู้ผลิต AdBlue รายแรกของประเทศไทย

Pingback: Buy browning firearms Online

Pingback: garbage SEO search engine

Pingback: putas a domicilio malaga

Pingback: โอลี่แฟนxxx

Pingback: scam site: beware do not send money or do business with this site. 100% scam!

Pingback: คลินิกปลูกผม

Pingback: kayak

Pingback: outdoor furniture bangkok

Pingback: jarisakti

Pingback: ข่าวบอล

Pingback: เดิมพันอีสปอร์ต LSM99

Pingback: แทงหวย

Pingback: คาสิโนสด

Pingback: Fryd liquid diamonds

Pingback: unicvv

Pingback: 무료 영화 다시보기

Pingback: dragongaming

Pingback: เซ็กซี่บาคาร่า

Pingback: Best magic mushroom shop Melbourne

Pingback: รับซื้อรถยุโรป

Pingback: mp3 juices

Pingback: sbobet

Pingback: Avery Albino Mushroom

Pingback: buy marijuana online legally,

Pingback: สล็อตวอเลท

Pingback: Chaturbate En La Oficina

Pingback: DevOps Consultation

Pingback: relx

Pingback: 쿠쿠티비

Pingback: Auto Glass marketing ideas

Pingback: exchange mail fiyatı