BY KRISTEN ANCILLOTTI | Every other year, the Whitney Museum of American Art (99 Gansevoort St. btw. Washington St. & 10th Ave.) presents the Whitney Biennial, an exhibition that shares what is happening in American art at the current moment, across the mediums of painting, sculpture, installation, film and video, photography, performance, and sound.

The Whitney is devoted to American art, particularly that of living artists, and its founder, Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney, began the tradition of the Biennial in 1932. From 1937 to 1972, the museum offered yearly exhibitions they called Annuals, then switched to the present-day format.

Now in its 79th iteration, the Whitney Biennial 2019 features the work of 75 artists, most under the age of 40, and not only reflects the current state of art, but the current state of the country.

“I think the themes that tie this exhibition together are race, gender, equality, and what constitutes a community,” said Roberta Krakoff, a Whitney docent. “Many of the artists in this show do what I call ‘mining history,’ that is, looking at historical documents or reading about history to understand the present and perhaps even understand the future.”

The art showcased in the Biennial had to have been produced in the last two years, and some pieces were made specifically for the show. Curators Jane Panetta and Rujeko Hockley were tasked with visiting hundreds of studios to cull the best representation of what is contemporary.

In their curatorial statement, Panetta and Hockley referred to the past year and a half as they made those visits as “an undeniably intense and polarized time in this country” and said that, “Although much of the work presented here is steeped in sociopolitical concerns, the cumulative effect is open-ended and hopeful.”

Elise Pustilnik, who was guiding the tour on the fifth floor, told Chelsea Community News that she was from the first class of docents, and she has worked for the Whitney for 35 years. She pointed out the continued relevance of the art seen in this year’s exhibition. “It’s rather interesting to me that many of them are as ripe at this particular moment as they were when they were probably conceived,” she said.

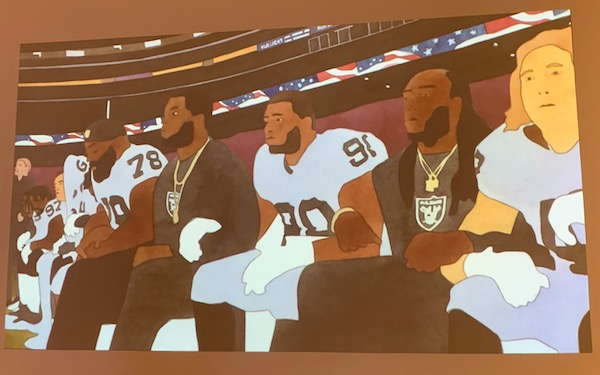

One such pertinent piece was National Anthem, by Kota Ezawa, a large-scale composition that greets visitors to the fifth floor of the museum. It is an animated work created from watercolor paintings, depicting football players kneeling in protest of police violence against unarmed Black men.

The protest movement was started in 2016 by Colin Kaepernick and adopted by other football players, and the act served as a lightning rod of controversy for those who would misrepresent what the protest was about. The work is visually arresting, but it is the pairing with a mournful, dirge-like version of “The Star-Spangled Banner” that makes the message truly hit home.

Continuing the themes of the 2019 Biennial is a bronze sculpture entitled Stick, by Simone Leigh. She is a trained ceramist who fashioned her sculpture of a woman out of bronze, flipping on its head the stereotype that bronze is a masculine material. Leigh drew on references from West African sculpture and architecture, and attempted to upend the idea that Black women are to be used in service to other people, according to Hockley’s narration of the piece.

This year’s Biennial also differs in how the art was produced. “It is an exhibit that looks to the handmade in many places,” said Pustilnik. “There are many artists who are using craft techniques in the works that they create, so the idea of mass production and hand production has come to the fore in this particular installation as well.”

Jeffrey Gibson, a Native American gay man, designed handmade garments associated with the Ghost Dance movement, using beadwork, fringe, and ribbons, as well as the use of a range of rainbow colors, in a nod to queer club culture. His work People Like Us reflects the use of clothing in the Ghost Dance movement as a form of expression and protection from the world.

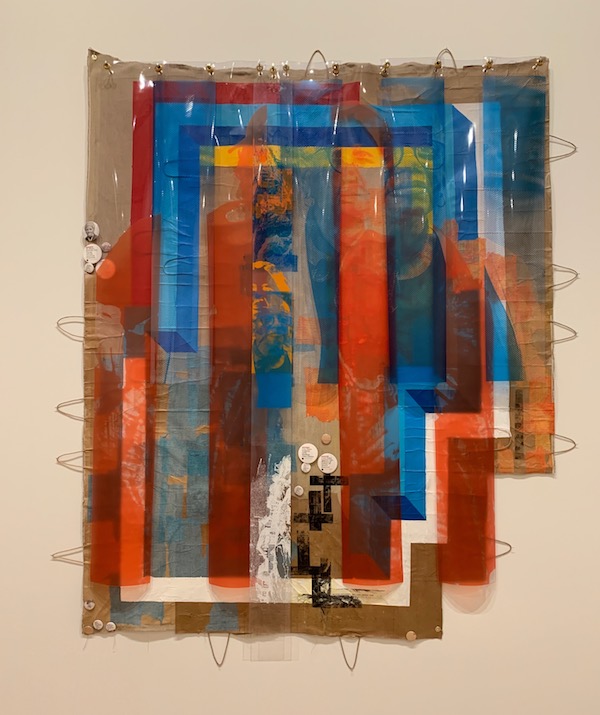

Especially relevant to New York City is Tomashi Jackson’s work on displacement in New York. She has three pieces in the exhibition, and her creations are made from found materials like paper bags, food wrappers, and vinyl insulation strips. Krakoff explained that the use of shopping bags represents the idea of sudden displacement—when a person without money is forced to move, they often must use shopping bags in place of a suitcase.

Jackson is one of a number of artists branching out from their usual medium to make a point specific to the Biennial. “She is not primarily known for collages, but she wanted to talk about both history and what’s going on currently in terms of the displacement of communities of color, and people who are economically very challenged,” said Krakoff.

The exhibition presented contemporary art with layers of symbolism, some more apparent than others.

“It’s a subtle show,” said Pustilnik. “The critiques are here. The damning is here. But it is much more integral to the work and not so blatant as it has been in some of our other Biennials.”

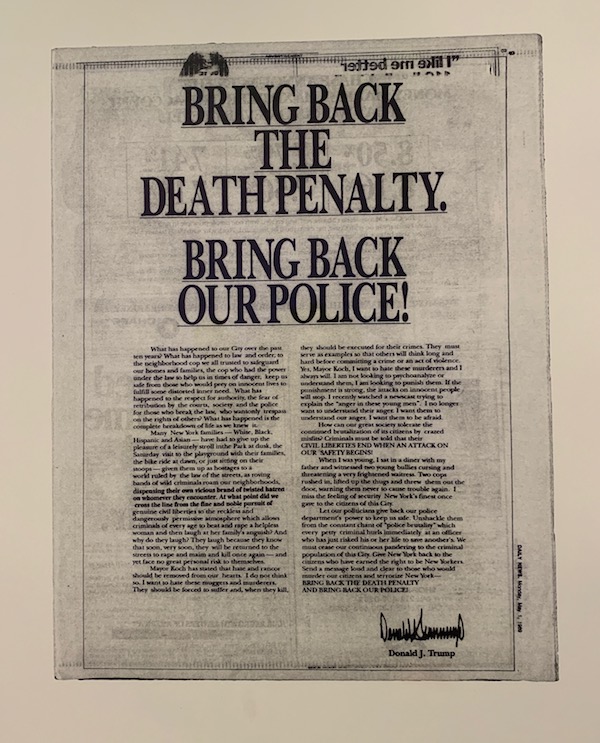

One subtle piece that spoke for itself, and was damning indeed, was Alexandra Bell’s series of prints, No Humans Involved: After Sylvia Wynter. Bell’s work looks at selected articles from the New York Daily News coverage of the 1989 Central Park Five case. This case is currently at the forefront of many people’s minds, due to the Netflix film When They See Us, as well as rhetoric coming from the current president. The Central Park Five were five boys of color who were wrongfully convicted of the rape and assault of a white woman in Central Park.

Bell’s prints, through the use of highlighting and redacting certain items, shows how language can be used to paint any picture, and points out the need for journalists to assess how they are wielding that power. The title No Humans Involved references an essay written by Sylvia Wynter in the wake of the L.A. riots, when it was reported that public officials used the acronym “NHI,” or “No Humans Involved,” when discussing cases involving young Black men.

The exhibition is understated, but unforgettable. Whitney Biennial 2019 was entirely planned during a period of turmoil for America, and it shows. It can, at times, be a heavy experience, but it feels cathartic to see fears and anxieties addressed as a collective. It is also worthy of celebration for providing a diverse group of artists the space to say exactly what they want to say, in the way they want to say it—and the prescience of their work is striking. Pustilnik sees this foresight as a characteristic of the Whitney Biennial.

“The Biennial always affects and shows what is happening at the moment,” she said. “Looking back at it after the two years, you realize it very much predicted what was going to be.”

The Whitney Biennial is running through Sept. 22, 2019. You can purchase tickets online until midnight the night before your visit at whitney.org. Museum hours are Sunday through Thursday from 10:30am to 6pm; and Friday and Saturday from 10:30am to 10pm (The Whitney be will closed on Tuesdays, from September to June). Tours for the Biennial on Floor 5 run Monday through Thursday at 1pm and 3pm; Friday at 7:30pm; and Saturday and Sunday at 1pm and 3:30pm. On Floor 6, they run Monday through Thursday at 2pm; no tour on Fridays; and Saturday and Sunday at 2pm. Admission prices are $25 for Adults, $18 for Seniors, Students, and Visitors with Disabilities (with free admission for one accompanying care partner), and free for members and people 18 and Under. Admission is Pay-What-You-Wish on Fridays, from 7pm to 10pm.

Chelsea Community News is made possible with the help of our awesome advertisers, and the support of our readers. If you like what you see, please consider taking part in our GoFundMe campaign (click here). To make a direct donation, give feedback about the site, or send a Letter to The Editor, email us at Scott@chelseacommunitynews.com.

Pingback: mushroom tea australia

Pingback: poolvilla pattaya

Pingback: xo666

Pingback: แทงบอลออนไลน์ ขั้นต่ำ 10 บาท

Pingback: ทำความรู้จักกับ บริษัท KA GAMING

Pingback: Codeless Software Testing Tool

Pingback: bonanza178

Pingback: superkaya88

Pingback: college degrees are worthless

Pingback: สล็อต ฝากถอน true wallet เว็บตรง 888pg

Pingback: aksara178

Pingback: 티비위키

Pingback: เช่ารถหาดใหญ่

Pingback: golden teacher mushroom size,

Pingback: benelli firearms guns

Pingback: https://ytmp3.lu

Pingback: Feuilleter

Pingback: Hidden Wiki

Pingback: passive income

Pingback: sbobet

Pingback: bullet journal template

Pingback: Visit This Link

Pingback: buy shroom chocolate

Pingback: https://colourcee.bet/

Pingback: magic mushroom grow kit,

Pingback: stucco repair

Pingback: as.healthhublot.com

Pingback: fullz dumps

Pingback: สล็อตแตกง่าย

Pingback: sexy girls of youtube

Pingback: cc dumps tutorial

Pingback: cvv dumps shop

Pingback: exchange online price

Pingback: Digital Transformation services consulting company

Pingback: Server Teknik Destek

Pingback: W88

Pingback: sunucu teknik destek