BY GERALD BUSBY | From the age of three, when I could barely reach the keyboard of our tall rosewood piano with my tiny straight fingers, I loved every sound it made, musical or mechnical. Mother’s Crown Upright Parlor Grand had been a wedding gift from her eight sisters, and a brother they called Peach. The piano was bought from the 1917 Sears Roebuck catalogue, and it was delivered by train in a big wooden crate. With pride and a touch of melancholy, mother told how it arrived at her front door in a horse-drawn wagon and how it took four men to get it into the house. That was my parents first home in Spur, Texas.

The piano had a player mechanism you had to pump with your feet. One of the paper rolls with thousands of minute holes punched in it was The Old Rugged Cross, mother’s favorite hymn. She would sit at the piano, and, without even looking at the keyboard, and reached back to clutch the bench to balance herself as she pedaled. It didn’t seem to bother her that the rhythm of her pedaling didn’t match the rhythm of the hymn. Her lips formed the words that rhythmically fit the melody issuing from the piano … “and exchange it some day for a crown.”

Nely Mae Arnold, mother’s maiden name, was the youngest of ten siblings, eight sisters and a brother they called Peach. Edna, the eldest, taught Nely Mae to play the piano and read music. None of the other sisters were musical except for Zada, who sang alto in the church choir. The first few years after mother got her piano, she played it herself or pedaled her favorite tunes. Then the rigors of housekeeping and raising two sons, James and Marion, absorbed her time and energy. Rheumatoid arthritis also began its painful development in mother’s knees and knuckles, the latter amounting to an assault on her proudest distinction in the Arnold family, playing the piano. “The Lord gave me a home and children, and a piano that plays itself to relieve my suffering,” she would say rubbing her swollen knuckles. At 35, she had all her teeth pulled believing it would ease her pain. Instead it got steadily worse.

Fifteen years later at our home in Tyler, Texas, I viewed mother’s unvarnished redwood piano as a wondrous toy, and I’d pedal it for hours just to see the keys go up and down as air passed through tiny holes in the paper rolls. That fascinated me more than the tunes it played. I watched the piano play itself from the time I was able to reach the pedals, and I memorized the top and bottom notes of every song. With my young straight fingers, I followed the mechanical action as the keys went down. My father liked to show me off to neighbors. “He knows every song that this thing can play, and he knows the words too,” he told them.

Mother had printed sheets of music for several songs on the piano rolls. Anyone who could read music could sing along. One was, “Cut yourself a piece of cake and make yourself at home. I’m sorry that I burned the steak, but cake is more high-toned.” The second was, ”Maggie, come right upstairs . . . Maggie, them stairs ain’t chairs.” The words described a young couple cuddling on the stairs as the girl’s mother sternly watched them from the landing above. The words reminded me of mother’s righteous tone, and I easily identified with the thrill of trying to get away with something naughty.

My father’s brother, Uncle Ben, and his wife, Aunt Jody, had vinyl 78 rpm discs of both these songs, and I always asked to hear them when we visited. I loved to turn the crank on their Victrola, and Aunt Jody invariably cautioned me, “Not too tight. You might break the spring.” The speaker horn, make of cardboard painted black with gold flourishes, fascinated me, and I couldn’t take my eyes off it while the records were playing.

Everyone in my family except for my father had some intimate relationship with mother’s Crown Parlor Upright piano. It was at the center of family gatherings in our living room, and it was where each of us came to express ourselves, both when we were alone and when we entertained others. After my piano lessons began with Norma Rae Killingsworth, my sister’s friend, I practiced two or three hours a day.

Juana Mae had a natural and engaging singing voice. She was an alto, and I was her accompanist. She loved Deep Purple and sang it on pitch with a steady vibrato. She always sang the alto solos in Handel’s Messiah with our church choir at Christmas, but she lacked musical finesse and was terribly disappointed when she failed an audition at WFAA, the NBC-radio affiliate in Dallas. Her favorite singer was Ginny Simms accompanied by Kay Kyser and his “Band of Renown.” Their World War II-era musical arrangements were intensely sentimental and were performed with lots of vibrato in the saxophones. Many songs referred to loved ones away from home.

My sister wrote the lyrics and music for a song called Lovely Liola. It had a noticeable lesbian subtext—“Lovely Liola, you’re the queen of my heart. Lovely Liola, say we’ll never part.” It was dedicated to Ginny Simms, who sang on a record my sister played over and over, “I love you so madly; I need your love so badly; but I don’t stand a ghost of a chance with you.” Juana Mae sent her am ardent fan letter with a handwritten copy of the song. After a few weeks, an autographed photo of Ginny Simms arrived in the mail inscribed, “To Juana Mae—Thanks for your thoughtful gift. All my best always, Ginny Simms.” Juana had it framed and hung it on the wall next to her bed. She took it with her to Baylor three years later.

My first piano teacher, Norma Rae Killingsworth, lived just a few blocks from our house. Lessons were 50 cents and lasted 30 minutes. She taught all her students to play the same piece, March of the Dwarfs. I played it louder and faster than anyone else, and the mother of another student, waiting to take her lesson after mine, complained that my playing was too loud and made her daughter nervous. Norma Rae had a Baldwin 5-foot, 2-inch baby grand with a walnut finish. The lid was always down, covered with a paisley shawl covered with small porcelain figurines. More than once Norma Rae’s mother stuck her head in the room when my playing made the figurines on the piano rattle. “We don’t want to wake your father,” she said in a forced whisper, not looking at anyone in particular as she closed the door with a decisive click.

It was at church that I developed my performance skills as a pianist, accompanying congregational singing at the Sunday night service. My style was heavily influenced by the gospel music of the Old Fashioned Revival Hour, broadcast weekly on the radio shows from Pasadena, California. An organist played the gospel songs in a straightforward manner, and the pianist embellished the basic harmonies with scales, octaves, and arpeggios.

At my church, First Baptist in downtown Tyler, Ralph Parker, was the organist, and I was the pianist. Ralph’s musicianship was shaky and unpredictable. In the middle of a hymn, he would lose his place and just hold a chord as though he’d gone to sleep. Everyone knew what was happening and would keep singing until he found his place and got back into rhythm. I filled in the rhythmic gaps with my melismatic flourishes. While plates were being passed to collect money from congregants, I played solo piano improvisations based on more meditative hymns. I was also the pianist for the church’s radio show, The Heaven And Home Hour. I improvised on hymns like In the Garden, a song about being alone with Jesus.

In 1955, I went as a piano major to Baylor University in Waco, Texas. I was always on the lookout for an opportunity to play the Steinway “D” concert grand on the stage of the recital hall. No student was allowed to practice on it, but I had to. On holidays, I’d break into the music building, climbing through an unlocked bathroom window in the music building, to get at that Steinway. I would remove the black leatherette cover and raise the lid as high as it would go. Then, seating myself on the adjustable concert bench, I’d play a loud, arpeggiated chord, holding the sustaining pedal down until the sound died away. The thrill was visceral.

The next year I entered the Yale School of Music as a piano major. Myra Hess (1890-1965) the great British pianist, played, at Sprague Hall, a solo recital that included Robert Schumann’s Symphonic Variations. Her playing transformed my perception of touch. She could play softer than anyone I’d ever heard, and every note, no matter how soft, had a “ping,” a solidity that resonated to the back of the recital hall. Myra Hess’ teacher at the Royal Academy of Music, Tobias Matthay, taught her to play as though she were rolling an orange evenly over the keys, producing a velvety sound.

Every key touched the bottom of the key bed, and every note was seamlessly connected to the next. It was like a singer’s voice flowing smoothly from one note to the next with continuous sound. I remember forgetting that there were hammers percussively hitting strings. I heard only musical phrases that had shape and nuance and seemed to breathe.

The Italian piano virtuoso, Arturo Benedietti Michelangeli (1920-1995), also possessed a mesmerizing touch, especially in his performance of Ravel’s Gaspard de la Nuit. He kept his wrists low and his fingers deep into the keys. His thumbs were folded under, and his hands never left the keyboard. He had the uncanny ability to make a perfect diminuendo, like slowly turning a knob to decrease the volume of sound. He could even do it trilling two adjacent notes.

My first piano teacher to make me aware of the varieties of touch, Oscar Ziegler, told me I needed to adjust the height of my bench, sit up straight, and lean into the keyboard to “find” my fingers in the action of the piano. It was necessary to relax the muscles of my arms and hands to feel the vibration of every note I played through the conduit of the keyboard.

Everyone who plays the piano in public develops a persona at the keyboard. The mind and muscles of the body remember the overriding emotion when the fingers first learned the notes. My development as a composer corresponded to my willingness to get away from visual, tactile, and emotional connections I had with the piano keyboard. It was frightening at first, and I was uneasy to create music by being still and listening for the next note, rather than trying to decide what the next note should be.

I still needed the feel of my fingers on the keyboard when I composed Runes for Paul Taylor, the summer of 1975. He originally asked me for a chamber orchestra suite, and I said yes, though I really had no choice but to improvise the entire dance suite at the piano. Paul and I had just six weeks, the duration of his company’s summer residency at Lake Placid, New York, to complete the dance.

After five weeks I had written a suite in seven movements for solo piano, and the dance Paul created to my music was an immediate success. To my relief, Paul said Runes should remain a solo piano piece and not be orchestrated. Paul invited me to go with his company to Paris for the European premier at the former Sarah Bernhardt Theater, now the Theatre de la Ville. Runes launched my career as a composer and marked the end of my total dependence on the black and white notes of the piano keyboard to write music.

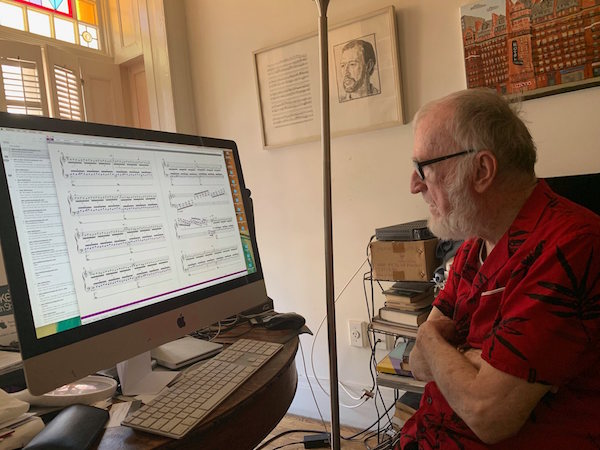

But the keyboard remains my visual template for recognizing sounds. I “see” the pitch of the notes as patterns on the black and white keys when a truck on 23rd Street blows its horn passing outside my windows at the Chelsea Hotel. I no longer play my worn-out, 40-year-old upright Kawai that sits directly across from my bed. It’s really an invaluable relic of my musical history that I often look at and occasionally touch gently as I walk by.

Chelsea Community News is made possible with the help of our awesome advertisers, and the support of our readers. If you like what you see, please consider taking part in our GoFundMe campaign (click here). To make a direct donation, give feedback about the site, or send a Letter to The Editor, email us at Scott@chelseacommunitynews.com.

Pingback: หวยรัฐบาลไทย

Pingback: ติดเน็ตบ้าน เอไอเอส

Pingback: ร้านขายยา

Pingback: steenslagfolie

Pingback: ยิง sms

Pingback: game sex

Pingback: มวยไทยมีกติกาในการเล่นอย่างไรบ้าง

Pingback: buy weed online in Europe

Pingback: white cherry runtz strain online

Pingback: fetichista málaga

Pingback: สล็อตออนไลน์

Pingback: browning auto 5

Pingback: pk789 สล็อต

Pingback: https://analytics.rrr.org.au/event?target=https://bramptoncannabis.store/

Pingback: สมัคร lsm99

Pingback: 20197 Homes for Sale

Pingback: Automation Testing tools

Pingback: weed delivery toronto

Pingback: pg slot

Pingback: try this web-site

Pingback: Buy Albino Penis Envy Mushrooms For sale Denver

Pingback: weblink

Pingback: earn passive income

Pingback: bergen county therapy

Pingback: Home Page

Pingback: Florestan

Pingback: visit the website

Pingback: nova88

Pingback: สล็อตวอเลท

Pingback: nova88

Pingback: Buy Runtz online

Pingback: kardinal stick

Pingback: wow slot

Pingback: pair programming

Pingback: Memory and Gratitude – Chelsea Community News

Pingback: Glo Carts

Pingback: Microsoft exchange mail

Pingback: instagram hack

Pingback: evden Çalışma