BY RANIA RICHARDSON | New York City teachers went back to school last week, and students are scheduled to return on Monday, September 21. With widespread dissatisfaction regarding reopening plans, it is unclear if that date will hold. Among those vocalizing their unique concerns are stakeholders in a key school district in the New York City Department of Education, known as District 75 (D75).

There are almost 25,000 students comprise the district that provides highly specialized instructional support to young people with significant challenges—among them, autism spectrum disorders, cognitive delays, emotional disturbances, sensory impairments, and multiple disabilities, for which students receive specialized support. About 80 percent of D75 students are Hispanic or Black, and 75 percent are male.

All NYC public schools serve children with disabilities, and some students with special needs are educated in the same classroom as their non-disabled peers. D75 students generally have multiple or profound challenges, and are better served in their focused district.

Day-by-day Mayor Bill de Blasio is announcing updates on school reopening, and the details continue to evolve. Currently, among the issues of concern in D75, is protection from COVID-19 in what are normally highly interactive classrooms. In addition to teachers, there are paraprofessionals, guidance counselors, secretaries, counselors, social workers, nurses, and speech, occupational, and physical therapists in D75, who are on the front lines.

An educational and political activist, Mindy Rosier-Rayburn, has been in the classroom as a special education teacher for 23 years, 14 with the DOE. (She is also president of the Chelsea Reform Democratic Club, a longtime advertiser with this website.)

At her elementary school in Harlem, about half of her students are on the autism spectrum, and half are emotionally disturbed/learning disabled. For school year 2020-21, all DOE teachers were able to choose to give instruction in the blended (combination of in-person and remote) or 100 percent remote environment. She chose the remote option, as a medical accommodation.

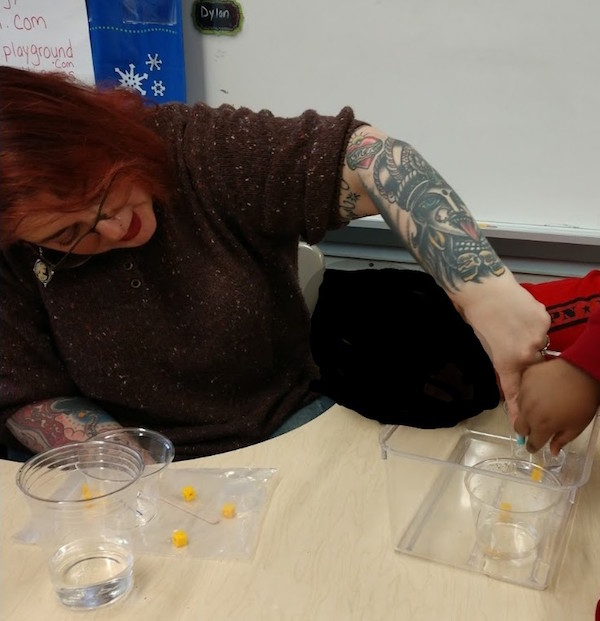

In teaching science, Rosier-Rayburn uses hands-on techniques to break the material down to meet the level of the students.

“The physical aspect is very important in special education,” she said. “We use ‘hand-over-hand’ to teach a child how to hold a pencil, for example. A speech therapist may touch a child’s chin.” Physical prompting and physical engagement are necessary to complete the work, even more so in services such as physical and occupational therapy.

Additionally, “We are all touching the same things on tabletops, including books,” she said, and wondered if tactile items will be provided at all in the upcoming school year. “And who is going to clean the floor and vacuum the carpet for storytime?”

Interpersonal space is reduced in the special education classroom. Teachers get coughed on and sneezed on every day. Said Rosier-Rayburn, “We come in contact with body fluids all the time. There are spitters, physically aggressive children, and those who put their fingers in their nose. Some kids are runners, and try to push you out of the way to get out of the room. How do we protect ourselves against the virus?”

Self-injurious children might bang their heads on the social distancing barriers. Over the course of day, the plastic could become “a petri dish.” She suggested face shields as the minimum protection.

“Some children are very huggy and affectionate. We won’t be able to hug our children like we used to! We make our schools a home-away-from-home. This breaks our hearts,” she said.

One piece of personal protective equipment (PPE) per day for every student and staff is an “insane” amount, and in this environment, more would be necessary. There are students who might play with, chew, or shove a mask in their nose or ear.

In describing how she came to her line of work, Rosier-Rayburn said that during training to be a kindergarten teacher, she visited a special education class.

“This adorable girl with Down syndrome befriended me. I’ll never forget her huge smile. She put her hands up in front of her so I could connect with her, with my hands. It was a very simple but touching gesture. This little girl changed my path. I knew in that moment, special education was my calling,” she said.

Grisel Cardona was recently promoted to vice president of the Citywide Council for District 75 (CCD75), a self-described “Education Council representing students and families of District 75, all students with special needs and/or an IEP [Individualized Education Program].” The organization’s parents elect its parent council members. Cardona’s goal is to give voice to D75, and “to disrupt and dismantle the many inequities” facing children with disabilities.

Cardona’s son, Christopher, a fifth grader in D75, loves working on computer art. Did he enjoy in-person classes before the pandemic? “Of course!” he replied, “I liked it a lot.” He loved being around his friends, and his teacher was “amazing.”

Nevertheless, for the upcoming semester, Cardona chose 100 percent remote learning. She bought a table to look like a school, and will recreate gym activities in the park. Christopher has mixed feelings about not learning in-person. The considerations were many, but the decision was simple.

“We need to make sure safety comes first,” Cardona said. “But in schools, with all the budget cuts, who knows? When COVID happened, it started a nightmare we can’t get out of.”

Her home borough, the Bronx, “was hit hard.” She got the virus in April, and still feels some lingering effects. With extreme caution, she cared for her three young children. She “bubbled” herself up with a face shield, wore gloves while cooking, showered often, and slept in the living room. “Don’t come in!” she would yell. Through it, the children never caught the virus. Still, she fears that school could be a source.

“There are kids who don’t understand what’s going on, or what a virus is. They may say, ‘I don’t want to die.’ It’s a process to get them through this,” she said, adding, “Our reopening should be unique. Parents are scared and confused. Some say their kids need in-person learning, others say their children can’t handle the iPad at home. One parent said their child had regressed, had been improving with therapy and went back to using a wheel chair during the shutdown.”

Wearing a mask is difficult for some children, due to sensory overload. Head-to-toe PPE for educators would not work because, Cardona said, “the children might see them as monsters.”

She continued, “Some kids are afraid to go downstairs by themselves, some are diapered, who is helping them? Will there be the usual shared books or manipulatives? What about cleaning them? There are so many unanswered questions and unresolved issues, special ed teachers don’t want to go back in.”

Barely joking she said, “Get ready for a world war.”

Lori Podvesker is the policy director of INCLUDEnyc, an independent non-profit that helps families who have kids with disabilities. She is also the mother of a teenager in D75.

Podvesker said, “My son is delightful, but a handful, and not very independent.” Jack has intellectual disabilities, and attends a school that focuses on the performing arts. Like many students in D75, he is in an ungraded class.

“Transitions are very hard,” she said, and, echoing Cardona’s words, added, “When schools shut down in March, there was pandemonium. Everyone was traumatized.”

Jack’s abilities regressed: He lost writing, math, and social skills. For the upcoming semester, Podvesker chose 100 percent remote learning for her son, for logistical reasons among others, because his two mothers work full-time.

Jack misses his teachers, and seeing the same people on a regular basis. There is a teacher shortage now, especially in D75.

“The retention rate for special needs teachers is very high,” said Podvesker. “The teachers tend to stay longer. They are committed, loving, excellent. Because the attrition rate is low, there is a high percent who are older, and, as a result, seek accommodation.”

(Reasonable accommodations are modifications or adjustments to a job or work environment to enable an employee to perform essential job functions. In this case, it could mean choosing 100 percent remote teaching.)

“School is a community,” Podvesker said. “It’s like an extended family. In the pandemic, we are very lucky to have been living in Brooklyn for a long time, on a street with lots of neighbors.”

On Aug. 26, Mayor Bill de Blasio, First Lady Chirlane McCray, and Schools Chancellor Richard A. Carranza announced Bridge to School, a citywide 2020-21 school year initiative to address the social and emotional health of students in response to the trauma from the COVID-19 crisis.

Podvesker is happy that the DOE is making this a priority for all 1.1 million students in the system, as those skills are “just as valuable as academic skills.”

She said, “All kids will become aware of different life situations and trauma. It will be paramount to the success of students. They will learn empathy for others, and be informed of students with disabilities.”

NOTE: In a letter sent to D75 staff on Sept. 11 regarding school health and safety measures, District 75 Superintendent Ketler Louissaint wrote, “…we know that you are re-entering your buildings not only with excitement and anticipation of reconnecting with colleagues and students, but also with many questions regarding protocols and expectations to maintain a safe and healthy environment…” The five-page document outlines procedures, and indicates that custodian engineers will ensure a 30-day supply of PPE for their buildings and will implement wiping down surfaces throughout the day and disinfecting with electrostatic backpack sprayers at night.

Chelsea Community News is made possible with the help of our awesome advertisers, and the support of our readers. If you like what you see, please consider taking part in our GoFundMe campaign (click here). To make a direct donation, give feedback, or send a Letter to the Editor, email scott@chelseacommunitynews.com.

Pingback: apple fritter mkx cart

Pingback: ปั้มคนดูไลฟ์สด

Pingback: ทัวร์เวียดนาม

Pingback: ทางเข้าpg

Pingback: สล็อตเกาหลี

Pingback: cam

Pingback: jebjeed888

Pingback: ทางเข้าเกม SUPERSLOT เครดิตฟรี

Pingback: รับจัดงานอีเว้นท์

Pingback: เค้กดึงเงิน

Pingback: เว็บปั้มติดตาม

Pingback: essentials

Pingback: รวมเว็บพนันออนไลน์

Pingback: ลวดสลิง

Pingback: more information

Pingback: sahabat qq

Pingback: วิธีดูอัตราต่อรองบอล พร้อม ราคาบอลออนไลน์

Pingback: โปรแกรมพรีเมียร์ลีก

Pingback: รับผลิตป๊อปคอร์น

Pingback: ตารางบอล

Pingback: 다시보기

Pingback: empresa informática

Pingback: cz firearms for sale

Pingback: same day delivery weed toronto

Pingback: 토토달팽이

Pingback: Razor Crazy Cart Shift Blue/Black

Pingback: ดูหนัง

Pingback: แทงบอลโลก 2022

Pingback: hho hydrogen kit/47% Fuel-Saving Plug-N-Play HHO Kit HHO generator Hydrogen kits for cars trucks

Pingback: DevOps Consulting Companies

Pingback: สล็อตวอเลท

Pingback: Pgslot

Pingback: company website

Pingback: cvv dump