BY TRAV S.D. | For Black History Month, we present you with weekly slices of the Tenderloin, the now-defunct New York City neighborhood that at its furthest extent ran between 24th and 62nd Streets between Fifth and Eighth Avenues, thus overlapping with modern Chelsea. The Tenderloin was so-named by a local police captain who relished the nabe for its savory graft. In its heyday of the 1880s through the early 1910s, it was a nightlife mecca full of saloons, dance halls, gambling dens, and bordellos. Prior to the Jazz Age and the northward migration to Harlem and San Juan Hill (where Lincoln Center is now), it was also where much of NYC’s African American population resided. This month, we will celebrate several black showbiz heroes and pioneers who lived there.

George Walker (1873-1911) and Bert Williams (1874-1922) are important figures not only in show business history, but American culture as a whole. Williams, the more gifted and longer-living of the two, has been called the Jackie Robinson of American show business, but both were pathbreaking and influential. The pair met in 1893 while performing in saloons and minstrel shows in San Francisco’s Barbary Coast. Frisco, too, had a Tenderloin neighborhood, named after New York’s one. Early on, Williams, who was mixed-race and light-skinned, resorted to wearing blackface during performance, which was not uncommon for African American entertainers to do at the time. Initially, Williams would have preferred not to have done so. He was dignified and educated; he had initially gotten into show business to earn money for college. But the blackface dictated a broad, clownish character, a sad sack he called “The Jonah Man.” Walker, his cheerful and more streetwise comic partner, drove the plots of their sketches, much as Bud Abbott would later drive his routines with Lou Costello. The combination rapidly made a hit with audiences, and they gradually worked their way East.

Billed as “Two Real Coons,” the two traveled with their constantly improving act starting in 1896. In 1898 they were spotted by a scout in French Lick, Indiana and tapped to perform in a Broadway show The Gold Bug, which lasted one week at New York’s Casino Theatre. This was when they began to reside in the Tenderloin. A succession of prestige vaudeville gigs followed, though. Among the major local venues they played were Koster and Bial’s Music Hall, which was located at the present site of Macy’s; Proctor’s Fifth Avenue (at 28th Street); and Hammerstein’s Olympia (Times Square).

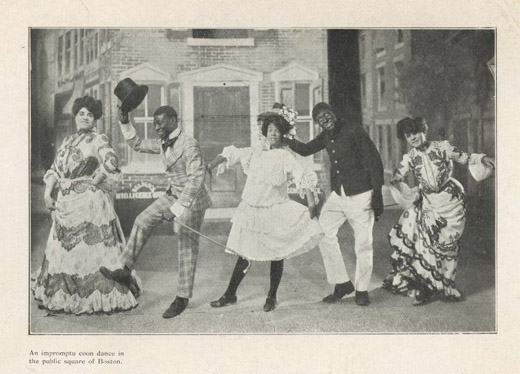

Williams and Walker were credited with introducing the cakewalk to mainstream America in their act, a popular dance that evolved from the minstrel show walkaround. Comical dancing became a highlight of their act, Walker high-stepping and lively, Williams, shuffling and clumsy. In 1898, they toured with Clorindy, or the Origin of the Cakewalk, a book musical that further helped to legitimize African Americans on stage. They followed this up with a tour of A Lucky Coon, a sort of compendium of their minstrel bits, in 1899.

On August 15, 1900, George Walker, walking through the Tenderloin with his friend, the performer and songwriter Ernest Hogan, was caught up in a violent race riot. An Irish policeman had been killed two days previously by an African American local due to a misunderstanding. A neighborhood-wide melee subsequently broke out between the Irish population, which had lived in the Tenderloin for a longer period of time, and the minority African Americans.

White mobs actively sought prominent African Americans to attack, Williams, Walker, and Hogan among them. Williams was at home; Hogan was badly beaten; Walker hid out all night in a storef the American South with a medicine show, were chased by a lynch mob and stripped of all their belongings including the clothes on their backs. New York it seems, could be just as hostile a place for African Americans as the former Confederacy. But it didn’t stop Walker and Williams from blazing numerous trails for others to follow.

In 1901, the pair made history by becoming the first black American recording artists, and the cylinders they cut sold well enough to put them among the first bestsellers, as well. They then went on to star in and produce many important musicals over the next several years, including The Sons of Ham (1901), In Dahomey, the first all-black musical to open on Broadway (1902-05), and Bandanaland (1908). In 1903, Williams and Walker became the first African Americans to give a command performance for an English Monarch (Edward VII). George Bernard Shaw said of their performance: “the best acting now in London is that of Williams and Walker in In Dahomey.”

But it couldn’t last forever. In 1908, Walker contracted syphilis, which in those days was without a treatment. By 1909, the condition was affecting his performance and though he struggled valiantly to control the symptoms, he began to stutter, forget his lines, and lose his motor control on stage. That year, he retired from the act. By 1911, he was dead.

For a brief while, his wife Aida Overton Walker (a dancer who had performed with the team for years), went on as his replacement in drag. After a period of uncertainty, Williams developed a solo act, and in so doing, revealed himself to be one of the great comic artists of the 20th century. In addition to his classic character songs like the famous Nobody, with its distinctive mix of pathos and humor, he also told dialect stories, (or “lies” as he called them) in the great tradition of African American folklore, and pantomime, which he claimed to have learned in Europe from a man named Pietro.

His “poker routine,” in which he silently portrayed every player in a card game, conveying several distinct characters right down to what hand each man was holding, was legendary (and, luckily, was preserved on film). He toured the country in vaudeville with this material, almost never receiving the top billing he deserved because of the prejudice of the times, although there times when he was next to closing at Proctor’s Fifth Avenue and Hammerstein’s.

From now, through the rest of his life, Williams was in the strange position of being hailed as a genius, universally beloved and respected by his colleagues, adored by his audiences… yet forced to leave the theatre by the back door, stay in separate “colored” hotels and boarding houses (in towns that had them), and avoid local troublemakers (including law enforcement officers) who relished making life hell for black people.

In 1910, Williams became the first major African American star in motion pictures, a series of one-reel silent shorts for Biograph. In 1911, Ziegfeld hired him for his Follies—the first black to be so honored. When most of the cast threatened to leave, Ziegfeld is reported to have said, “Go if you want to. I can replace every one of you, except the man you want me to fire. Though getting his foot in the door at Ziegfeld’s was an achievement, it didn’t spell the end of racism in his life.”

In the show, while given many chances to shine, they were plenty of times when the roles he was given to play were an unfortunate reflection of the attitudes of the times: red caps, cab drivers, or some other type of lackey to his white co-stars were the typical parts given to this grandson of a diplomat. The racism becomes even more risible when you contemplate the fact that Williams was one of the great performing geniuses of his day. Fortunately, there is just enough visual record to verify the contemporary raves. The best is the circa 1913 feature Lime Kiln Field Day, which only saw the light of day a few years ago when it premiered at the Museum of Modern Art.

In 1914, Williams headlined at the Palace Theatre, another first for an African American, and the very pinnacle of success for a vaudevillian. And then there were the two well-known film shorts, A Natural Born Killer (1916) and Fish (1916). Would there were more, but at least these exist to be studied and enjoyed.

Williams’ last years were spent working Ziegfeld shows and the Keith vaudeville circuit, but by the late teens his health began to fail. He died of a combination of heart failure and pneumonia while performing in Under the Bamboo Tree, a Shubert show in Detroit. He was only 47.

For more on George Walker, Adah Overton Walker, and Bert Williams, please click here to visit Travalanche. For Trav S.D.’s more extensive look at Williams and Walker (posted to Travalanche on Nov. 12, 2009), click here.

Chelsea Community News is made possible with the help of our awesome advertisers, and the support of our readers. If you like what you see, please consider taking part in our GoFundMe campaign (click here). To make a direct donation, give feedback, or send a Letter to the Editor, email scott@chelseacommunitynews.com.

Pingback: ซอฟต์แวร์บริหารงานบริการทำความสะอาด

Pingback: คาเฟ่อารีย์

Pingback: url

Pingback: เว็บหวยออนไลน์

Pingback: order crack coke locally

Pingback: Online medicatie kopen zonder recept bij het beste Benu apotheek alternatief in Amsterdam Rotterdam Utrecht Den Haag Eindhoven Groningen Tilburg Almere Breda Nijmegen Noord-Holland Zuid-Holland

Pingback: 비트코인구입

Pingback: Nineties OG 1.5g High Roller Pre-Roll

Pingback: visit the website

Pingback: Buy Revlimid Online

Pingback: Alexa Nikolas police report

Pingback: va juste à

Pingback: สล็อต pg เว็บตรง

Pingback: upx1688

Pingback: www.desirestonight.com/older-women-looking-for-men/

Pingback: snuscore

Pingback: buy guns online

Pingback: replica christian loubatin shoes red bottoms

Pingback: Contrat De Performeur Chaturbate

Pingback: Search Chaturbate Emoticons

Pingback: buy HK guns USA online

Pingback: HomeRite Windows and Doors - Window Installation Service

Pingback: บาคาร่า1688

Pingback: Glo Carts

Pingback: golden teacher dosage

Pingback: dumps site