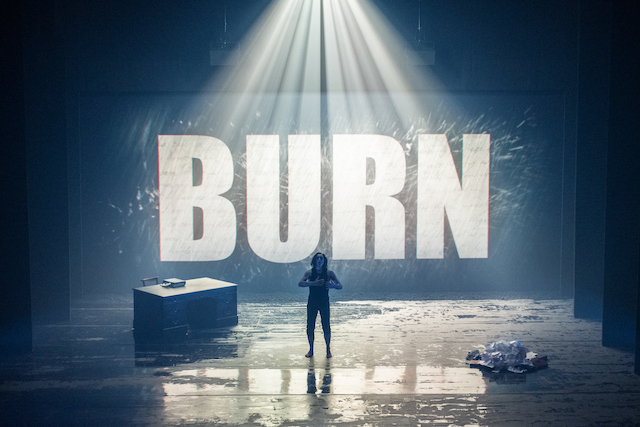

BY BONNIE ROSENSTOCK| Some minutes before Burn began, there was an epic river of a rainstorm, pelting leftward, seen on the back screen. Booming claps of thunder were heard, and lightning illuminated the sky, which gave just a hint of a mountainous backdrop. After it subsided, Alan Cumming appeared onstage dressed in black, dark eyeliner emphasizing his piercing eyes, jet black neck-length hair flowing as he sensuously shifted his upper body—arms and torso moving, feet planted in place. So begins the tale of Robert Burns, Scotland’s legendary national bard and beloved larger-than-life folk hero, a tale co-created by the legendary larger-than-life, multi-talented, multi-award-winning Cumming, Scotland’s proud progeny. (Was Burns born in a storm, or was it just for effect to symbolize his short, stormy life?)

Just weeks after its world premiere at the Edinburgh International Festival, Cumming brings the North American premiere to the Joyce Theater, September 20-25, which sold out within minutes (spotty individual seats were available for some remaining performances, as this review was published). In presenting his one-hour solo dance/theater piece, Cumming hopes to challenge the “biscuit tin” image of the bard (i.e., his face appears on lunchboxes) and present a more complex, nuanced look at his life by focusing on the (possibly bipolar) man himself—his successful ups as well as his depressive downs, poverty, loves, and losses.

The tale is told through a deep dive into his voluminous personal, unsparing correspondence and remarkable poetry, some written in the Scots language (difficult for Americans to understand), as well as the “light Scots dialect” of English, also a bit challenging. He also wrote in standard English, especially in his letters—all of which Cumming brings to light to flesh out Burns’s rarely explored inner life. The story is told in chronological order, the dates, names of places, people, and gorgeous scenery of farmhouses, forests, mountain ranges, spiraling white matter, a recurring white horse, writing segments, flashed on a large screen.

The first monologue gets to the heart of the matter:

Here Am I. You have doubtless heard my story, heard it with all its exaggerations. But I shall just beg a leisure moment of you until I tell my own story my own way.

My name has made a small noise in this country, but I am a poor, insignificant devil, unnoticed and unknown,

I have been all my life one of the rueful looking, long visaged sons of Disappointment.

I rarely hit where I aim, and if I want anything I am almost sure never to find it where I seek it.

For instance, if my pen-knife is needed, I pull out twenty things—a plough-wedge, a horse-nail, an old letter or a tattered rhyme—in short everything but my pen-knife, and that at last after a painful, fruitless search will be found in the unsuspected corner of an unsuspected pocket, as if on purpose thrust out of the way.

As he relates his life story, four ladies’ shoes drop on wires, which he addresses in turn. Burns was quite the ladies’ man, and he loved quite a few, some at the same time. His first child was with his mother’s maid, while he was in a relationship Jean Armour, but he also fell in love with Mary Campbell, whom he wanted to run away with to Jamaica. At some point, he takes off his wedding ring from Jean and puts it in Mary’s shoe. He marries Jean. From Jean’s shoe he pulls out two little shoes, his twins. Mary dies; petals fall from her shoe. Some exquisitely passionate letters and poetry result from these and other liaisons.

Four chairs slide onto stage, and it’s Edinburgh: December, 1786. He bows and addresses the chairs, his benefactors. A voiceover from the review of Henry Mackenzie in the Lounger, extolling his genius and relating his poverty and misfortune. As the review ensues, Burns realizes its condescending tone. He piles on costume after costume to try to please everyone. He collapses onto the floor. There are flashing lights. On the screen, words and phases flash: Pride and Passion. Hypochondria. Hypomania.

Cumming talks to a large dress that rises from the floor in a beacon of light. A happy time, Burns’s earnest correspondences with Frances Anna Dunlop, an occasional sponsor, but they have a falling out.

Cumming does a variation of a Scottish highland fling with elements of foot stomping. He recites a long poem of Scottish pride and patriotism:

I have no greater aim than to make leisurely pilgrimages through Caledonia [the Roman Empire Latin name for Scotland]. There is scarcely anything to which I am so feelingly alive as the honor and welfare of old Scotia [Latin placename for Scotland by the late Middle Ages], and as a Poet I have no higher enjoyment than singing her sons and daughters.

By the end of the show, he recites excerpts from letters and poems throughout his life, while he spins out of control. He drops to the ground, dead at age 37 from a heart condition.

After a standing ovation and taking his bows, Cumming comes out to sit at the edge of the stage with a drink in his hand and quietly recites Burns’s famous “Auld Lang Syne.” Cheers.

Cumming co-created the work with Olivier-winning choreographer Steven Hoggett. It was co-choreographed by Hoggett and Vicki Manderson, with video design by Andrzej Goulding and illusion design by Kevin Quantum. Associate Director was Shilpa T-Hyland. The remarkable music was composed by Anna Meredith.

Cumming, who is 20 years older than when Burns died, has a youthfulness and vitality that belies his 57 years. He spoke with choreographed gestures fitting to the words. His commanding stage presence was riveting.

Burns’s motto was, “I Dare!” The same can be said of Cumming.

Through Saturday, September 25. Remaining performances: Wed. at 7:30pm, Thurs./Fri. at 8pm, Sat. at 2pm & 8pm. At the Joyce Theater (175 Eighth Ave. at W. 19th St.). As of this writing, a handful of tickets remained for certain performances. To purchase online via the Joyce website, click here. By phone, call JoyceCharge at 212-242-0800, 12-6pm. Runtime is approximately 1 hour with no intermission. There is a free, post-performance “Curtain Chat” on Wed., Sept. 21. The Joyce Theater has lifted vaccination requirements. Masks are required at all times for visitors inside the theater, including performances. Click here for their full health & safety protocols.

Chelsea Community News is made possible with the help of our awesome advertisers, and the support of our readers. If you like what you see, please consider taking part in our GoFundMe campaign (click here). To make a direct donation, give feedback, or send a Letter to the Editor, email scott@chelseacommunitynews.com.

You must be logged in to post a comment Login