BY SCOTT STIFFLER | One cannot live by bread alone—but Amy Scherber, founder of Amy’s Bread, knew there was widespread appeal to this staple form of sustenance, enough to serve as the foundation for the small business she opened in 1992, staffed by five employees and located in Hell’s Kitchen.

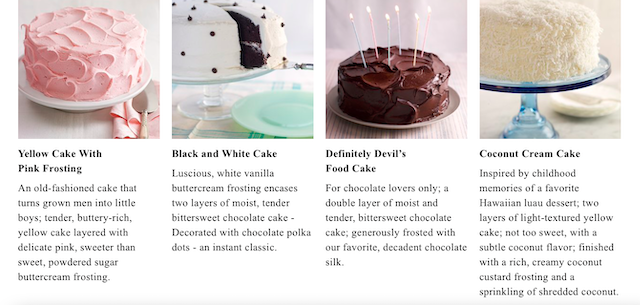

For 31 years, the store has stood at 672 Ninth Ave., while the sought-after roster of offerings has broadened its yeasty horizons to include pastries, scones, muffins, breakfast sandwiches, cakes, and more. But it’s the namesake product that ensures Amy’s Bread endures. “Crusty outside and chewy inside, and that beautiful aroma of the grain when you crack it open,” said Scherber, of bread’s layered, lasting appeal. “It’s an entire experience between the texture, the aroma, and the taste. You really can enjoy it with multiple senses.”

And people do. So much so, Amy’s Bread has expanded to include bread and pastry kitchens in Long Island City, Queens, retail cafes in Brooklyn, Hell’s Kitchen, and Chelsea, and cafes in the New York Public Library, Museum of the City of New York, and New York Design Center. The Chelsea Market store will be forever enshrined in history, having signed on as one of the now-iconic food hall’s original tenants.

Of course back then, Scherber’s leap-of-faith journey didn’t have the distinguished patina of business savvy that’s become more intense with each passing year. Harkening back to December of 1995, expansion-minded Scherber had a lock on Chelsea, having just settled on a ground floor retail space in the general vicinity of where Hudson Yards stands today. But fate, in the form of forward-thinking investor and Chelsea Market founder Irwin Cohen, had other plans.

The day after Scherber settled on a West Side warehouse co-op as the location of the next Amy’s Bread bakery, “Irwin Cohen called me on the phone and said, ‘I was talking to somebody who said you’re the best bread bakery.’ ” Cohen followed that compliment with a pitch to join the handful of tenants secured for his new business venture inside the onetime National Biscuit Company factory. Intrigued but by no means sold, Scherber told Cohen it “sounds amazing, but I am done with this [other West Chelsea] deal. He said, ‘Come with me. I’m going to walk you through it and you might change your mind.’ ” I thought, ‘Why not?’ ”

Hands-on Cohen arrived by van to whisk Scherber away to the under-construction site, where the two toured every explorable corner of Chelsea Market. “The building was empty,” recalled Scherber, except for “artists everywhere, making these sculptures and mosaics.”

Everybody Scherber encountered “was so nice,” she recalled. Even better was the telling fact that as the landlord approached, “they were all so happy to see Irwin.” At the end of the tour, Cohen “told me what the rent was, which was very reasonable—and I would have a windowed storefront.” That opportunity to attract passersby may have sealed the deal, as the Hudson Yards location was “just a warehouse, and I didn’t want that lack of connection with potential customers.”

Scherber went back to her Hell’s Kitchen store, ran the numbers, and assessed the pros and cons of renting at Chelsea Market vs. owning the warehouse space. “So I broke my deal with the place I bought the co-op from.” Freedom to put down stakes at Chelsea Market came at a price, though—the $25K Scherber had already sunk into the co-op was non-refundable. “That was a ton of money for me, at the time,” recalled Scherber, who had a long road ahead before the new location would bring in one penny of profit.

The lease on the Chelsea Market store was signed in early 1996, right after the new year. Over the next few months, said Scherber, “All these people called me, saying, ‘Are you serious? That’s a big space—what if it doesn’t go well?’ I thought, ‘I think this could be a really wonderful thing for us. I don’t really care if you don’t wanna go there. Other people will.’ But it took a certain amount of convincing. It was very scary over there.”

Despite little if any public gathering opportunities within visual range of the building, Scherber said her initial fears—actual and projected—dissipated the moment she literally saw the light. “He [Cohen] had put really bright lights on all sides, outside. So this building was a beacon of light… And my staff, the young women and men working the 3am shift, I felt like they were going to be able to take the subway and walk over there and be safe.”

By September of 1996, Scherber and crew had renovated the space and moved in—but ready for business didn’t translate into open for business. “They wouldn’t allow us to open our store,” she noted, because “That whole walkway was under construction. I realized I’m gonna lose a whole year waiting for everyone to get ready. That was a real struggle, but Irwin helped us with the rent. It was tricky.”

Once Amy’s Bread opened in the spring of 1997, along with the rest of Chelsea Market, Scherber said it took a good, solid year for people—particularly locals—to realize the building was their go-to place for food shopping. “You had the wine and the ingredients,” she said, of Chelsea Wine Vault and Buon’Italia. Manhattan Fruit Exchange, The Lobster Place, and Chelsea Market Baskets were among the other original tenants who were gaining a following. Their combined appeal soon saw the food hall’s navigable passageways swell with foot traffic from around the corner and around the world.

“Locals would come here to buy a lot of their groceries, and then stop at our place,” Scherber noted, adding, “and the people [workers from tenants] upstairs were wonderful, always coming down for lunch or stopping by at the start of their day.”

Scherber recalls those early years—when businesses began to find their footing and the customer base had yet to skewer toward tourism—as a time when long-lasting friendships formed at meetings where the retail tenants “would find ways to accomplish things we needed to do as a group.” These gatherings were also a time, said Scherber, when a quick scan of the room brought home “just how many women business owners there were. That’s part of what made being at Chelsea Market so special. I loved working with Mary Cleaver [owner, The Green Table]. She was always a great leader—a gatherer, helping to get everybody together. And then there was Sarabeth [Levine, of Sarabeth’s Bakery], who’s still there today.”

Scherber traces another narrative marker in Chelsea Market’s 25-year history to 2009/2010, when clientele began to favor “people from all around the world, really,” who had read the Chelsea Market reviews and made sure it was a stop on their tour of NYC experiences. June 11, 2009 was also a game-changer: That’s when the first section of the High Line opened to the public. All of a sudden, “more and more tourists came to the area. They would come to Chelsea Market to get their snacks, and disappear into the High Line.” Longtime tenants like The Lobster Place noticed this and “made their space a little more inviting to customers.” A few years later, noted Scherber, “We started hearing we had to reduce our space because Jamestown [an investment group that purchased a prevailing interest in 2003 and secured outright ownership of Chelsea Market in 2011] said they wanted to have more tenants. A lot of leases were up.”

Amy’s Bread was not immune to the changes taking place. Part of their reshuffle involved the loss of the store’s original selling point—the glass section that allowed passersby to witness the breadmaking process. “That was the customer’s connection to us,” said Scherber. “Without it, our sales plummeted.”

As dire as that sounds, those plummeting sales put us at just past the halfway point in the ongoing Amy’s Bread/Chelsea Market narrative. The years ahead would see the store’s featured offerings ebb and flow according to market mood, changing tastes, and shifting demands. (For example: Just as the loss of longtime upstairs tenants and the boom of breakfast options being offered by others nearby ate into Amy’s morning sales, the post-pandemic thinning of the retail herd saw renewed demand for the most important meal of the day.)

In the present day, says Scherber, “We’re still doing a lot of breakfast business,” by serving that all-important trifecta of locals, upstairs office workers, and out-of-towners for whom Chelsea Market is still a stop on the itinerary. “We make three different kinds of breakfast sandwiches, alongside our sourdough bagels,” says Scherber, noting those bagels have become the deciding factor in declaring breakfast to be the Chelsea Market store’s “busiest time of the day.” That other morning must-have is no slouch either, when it comes to drawing customers to the store—and ensuring they’ll be back. “What I tell people who are starting a small business is,” says Scherber, “you have to sell something people want multiple times a day—and for us, that’s coffee.” Amy’s Bread has offered different brands over the years, but their current java of choice—Seattle-based Fonte Coffee Roasters—may be here to stay, based on sales and customer feedback. “It does equally well as your standard hot coffee, espresso, or cold brew,” says Scherber, noting, “We sell a lot of it, because it tastes wonderful. It has a beautiful, complex aroma, and goes along really well with our other breakfast items.”

Scherber credits the breakfast cash cow combo as key to helping them come out of the pandemic slowdown reinvigorated and ready to meet the never-ending challenges of running a NYC small business. “You have to be a little flexible,” she says, when asked how Amy’s Bread has remained a Chelsea Market mainstay for a quarter century.

One thing that’s changed over the years—and stayed the same—is Scherber’s husband, Troy Rohne. Currently the VP (“He’s really more like the CFO,” says Scherber), Rohne has been with the company full-time since 2002. Early work as the bookkeeper, then time spent as a breadmaker and a segue into the sales side of Amy’s Bread gave Rohne the experience needed for what he does now. “Bookkeeping, billing, collecting, accounting, everything,” says Scherber. “He’s amazing.”

Taking a page from the hubby’s playbook, Scherber says being open to change, whether organic or compelled, is key to the company’s longevity. “We go with whatever people are looking for in a particular location. When we opened the first [Hell’s Kitchen] Amy’s Bread, people came in and said, “Don’t you have any cookies, cheesecake, sweet things?” If that’s what they want, we’ll fill the shelves with it… I learned that early on, and I’ve run with it over the years.”

Of those ever-accumulating years, Scherber said she often gets “nostalgic” about Chelsea Market, with ample triggers whenever she treads the ground level’s well-worn pathways. Although its design is best-known for evoking the Market’s industrial past, it’s the eccentric decorative flourishes that take Scherber back to that day in 1995 when Irwin Cohen himself gave her a guided tour of the new space. “I see those little sculptures tucked into different spots along the wall,” notes Scherber, “and the door handles in certain places, handles Irwin got from a bank, or that giant clock in the archway. He would collect crazy stuff,” she recalls, “by going to these huge outdoor flea markets in different states. He’d buy a truckload of artifacts and install them everywhere.”

In that regard, Chelsea Market remains a tribute to Cohen’s desire to create something utterly unique, but universally understood. “There have been a lot of indoor food halls since we made our debut,” says Scherber, “but they’ve never been able to accomplish what Chelsea Market does best, never duplicated the beauty in its bones. I’m really a big fan, and I feel just as strongly about it today as I did way back when.”

–END–

Chelsea Community News is an independent, hyperlocal news, arts, events, info, and opinion website made possible with the help of our awesome advertisers and the support of our readers. Our Promise: Never a paywall, no pop-up ads, all content is FREE. With that in mind, if circumstances allow, please consider taking part in our GoFundMe campaign (click here). To make a direct donation, give feedback, send a Letter to the Editor, or contact our founder/editor, send an email to Scott Stiffler, via scott@chelseacommunitynews.com.

To join our subscriber list, click here. It’s a free service provding regular (weekly, at least) Enewsletters containing links to recently published content. Subscribers also will be sent email with “Sponsored Content” in the subject line. That means it’s an exclusive message from one of our advertisers, whose support, like yours, allows us to offer all content free of charge.

You must be logged in to post a comment Login