BY MICHAEL MUSTO | In 1940s movies starring Mickey Rooney and Judy Garland, there’s usually a moment when someone exclaims, “Hey, kids, let’s put on a show! Daddy’ll let us use the barn!” That was sort of the feeling around the creation of my Motown revival band, the Must. Truth be told, I was coming off a head trauma in 1980 and wanted to reignite my taste for performing in order to perk up my stunned existence. My roommate, Courtney Johns, told me he played guitar, so together, we hatched the idea of a band, with me pushing for a Motown cover group because I grew up to the thrilling sound of the Supremes, Temptations, Four Tops, Stevie Wonder, and Marvin Gaye and Tammi Terrell and had never gotten beyond my affection for that era. Diana Ross was the ultimate entertainer to me—one with sparkle, pizzazz, and pathos to spare, someone who’d “reach out and touch somebody’s hand,” as long as they didn’t get too close. “Cultural appropriation” never occurred to me at this point—I just loved the music and wanted to add a gay male spin to all those great, often female-driven vocals that had saved my youth.

Tapping into a communal love of performing, I got my multifaceted journalistic colleagues to sing backup—the talented Brant Mewborn (After Dark) and the wonderfully deadpan Donna Peltin (Interview) and fab Mary Kaye Schilling (Us and later EW and New York magazine), plus the sultry Rhonda Granger on sax and Courtney and Ruben DuSemprun on guitars. (Other musicians who joined us through the years included Elliott Sharp and brothers John and David Rinehimer.)

We started rehearsing old Supremes songs, and I managed to book our debut for my splashy birthday party at the uptown club Hurrah for December 8, 1980. We billed the band as “the Must, featuring Toxic Shock”—meaning the backup singers—and the combination birthday bash/band debut appealed to the crowd, especially when a sycophant named Mark Busch dragged out a lavish birthday cake for all to enjoy, with my face on the center of it. As everyone ate my features, I realized that, though Busch had stolen cash from me one fateful night, at least he did so to spend it on my cake. That’s where I was in 1980. (And remember, I’d had a head trauma.)

Hurrah was packed and festive as we took the stage in a flamboyant burst of silliness, especially since at this point I had gotten an old college friend, Jay Padroff, to guest star on accordion, and I’d rented a viola (an obscure instrument I’d played in high school) for me to eke out a few notes on. Motown wasn’t really meant to be played on an accordion or a viola, but I was on fire and the backups were priceless—though as the show went on, I noticed some audience members looking a bit lost and some even streaming towards the exit. Were we that bad? No! I mean maybe! But what had actually happened was the horrifying buzz had gotten out that John Lennon had been shot at the nearby Dakota Apartments, so people were running there in tears for a candlelit vigil. And so, our debut was all sparkly and upbeat until it became dour and tragic.

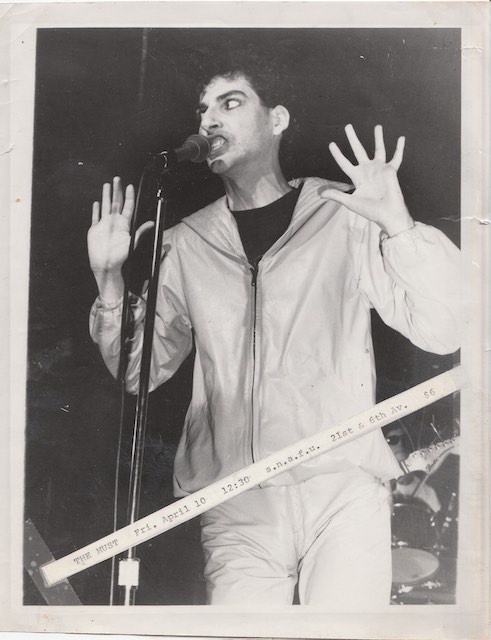

Amazingly, we managed to get more bookings. We did an all-star benefit at the new-wavey Mudd Club in Tribeca, where I got to duet with people like Nona Hendryx (of Labelle) and Ula Hedwig (of Bette Midler’s Harlettes), with rising star Marc Shaiman on the keys. We then played all over the place and faced a variety of mishaps—sound systems not working, money not forthcoming—but kept going, falsettos intact and arms a-flailing. At a sit-down club called S.N.A.F.U., the owner, Lewis Friedman, chastised me for handing in too long a guest list. (“This is a club, not a party,” he advised). But we had regulars—publicist Diane Collins and her friend Suzanne Soboloff were devoted—and we certainly weren’t going to charge them. Sometimes I thought we should pay them.

Luckily, the act was usually worth paying for, especially when we went frenetically over the top. Mark Busch (the thief/groupie) would cameo as Mama during I’m Living in Shame, the ultimate kitsch story song, in which Diana Ross expressed (fictional) shame over not having treated her mama well enough. As I sang about the heartbreak, Mark would come onstage in bargain-basement drag and scrub and clean everything in sight, dutifully rolling over and plotzing when I got the telegram saying, “Mama passed away while making homemade jam.” I wondered if he was scouring the stage for cash while he was at it.

The John Lennon-obsessed Mewborn (who wound up at Rolling Stone) had his own side projects and recorded A Love That Lasts Forever, a heartfelt tribute to the legendary Beatle who had died the night of our debut. I was surprised when Brant became involved with Rhonda Granger, though I loved Rhonda, who (intentionally) wore an upside down red dress and was the hit of the show with her blithe stage persona and fun sax wailing. She was very sax-y.

We played the Mudd Club again, this time without guest stars, but when I called owner Steve Mass for another booking after that, he said he’d heard from the bar help that we were not terribly good. What’s more, a friend informed me that in the glaring stage lighting, my makeup had made my skin look like an unpaved road. Oh, well. You learn, you lick your wounds, and you keep singing. Generally, we would open with Get Ready in falsetto, taunting the crowd with what they were in for. After my sardonic patter (“I was born a lesbian in Detroit…”), mock-dramatic numbers included You Really Got A Hold On Me, Love Child, Love Is Here And Now You’re Gone, I Want You Back, and some Mary Wells songs. I was trying to embrace the material and spoof it at the same time, though sometimes I just lost myself in the fantasy that I was Diana Ross.

At a downtown bank turned club called Chase Park, we were equally billed with someone named Madonna. She was up and coming and we were going nowhere. But like I said, we were equally billed! Unfortunately, Madge and her manager were far from inviting. They were laser focused on Madonna and only Madonna—we never got to sound check because she took so much time doing hers—but I guess it’s that kind of narcissism that helped her catapult out of that scene and into the stratosphere.

Our own ambitions were limited, but kind of endearing. We started introducing original material to the act, like a song I co-wrote with Carl D’Errico, a friend’s husband, who had cowritten It’s My Life for the Animals. Carl had been an integral part of the music scene in the very era my band was obsessed with—the 1960s! Also, singer/songwriter Cidny Bullens—who performed with Elton John and is on the soundtrack for Grease–produced us doing a cover of his bouncy song Jimmie, Give Me Your Love. (Cidny and I also wrote a song together called Detroit Music, about the enduring allure of the Motown sound.) Singing Jimmie in the studio, I was sick and feverish from something I had caught in Brazil, but bravely belted out the tune, including vampy ad libs towards the end. I hired a married couple to direct the video for the song, which appears on the 1984 collection Danspak II. But the wedded artistes were mad that I wouldn’t spring for $300 to rent a live pig and hold it in the video. The problem is I’m cheap, I don’t love animal abuse, and I would no doubt squirm even more than the pig would. Plus it had nothing whatsoever to do with the song anyway. This wasn’t Green Acres-A-Go-Go.

When I gloated about our new (pigless) video to a friend, he declared that I didn’t have a snowball’s chance of making it. That was harsh, but deep down I knew how competitive things were, and besides, an openly gay cover band with an occasional original song could only go so far, especially since I was more “Michael the gay” than Marvin Gaye. But I still liked the idea of at least trying, and besides, having a professional recording and video to send out helped us aim for better gigs.

And I was daring to live my dream, which was the original impetus for the band; to get out of my shell and just do it, for fun’s sake. That provided some joy, though the bittersweet experiences kept leaving an itching in my heart. One night, we had a wacky, interactive audience contest, and Broadway star and future Tony winner Andre DeShields won and got to perform with us the next time. Or I should say he had to perform with us—it was his prize, lol. Andre—who wanted to be called Lloyd Baltimore for his appearance—was great about the whole thing.

Unfortunately, the night he joined us onstage, a drunken club girl was loudly heckling us from the second we emerged, and she wouldn’t stop. I didn’t have the chops to handle her, and I hoped someone else would, but people later told me they thought it was part of the act! Like I would hire someone to stand there and call me names as I’m trying to sing. I could have just gotten a family member to do it for free!

Another night, at a Westchester dance club, Brant generously said that I had slayed the crowd with my vocals and banter. Alas, that same night, the club decided to stiff us. The Lord giveth. Of course, I was also capable of sabotaging myself. After a Pride gig at the multi-level rock 21st Street club Danceteria, another backup singer told me that my patter had been completely deadening and devoid of energy. In horror, I realized it was true. I was suffering horrible allergies all day and had been pretty much droning, prompting an audience cry of “Music!” (I.e., “Shut up and sing!”) I should have pumped myself with Benadryl, but I was afraid that would make things even worse. I can see why some rock stars take “uppers.”

Every performance was different, based on the club, the crowd, and our moods, and in the process, I became way more sensitive as to what’s expected of entertainers and how much is out of their hands as they valiantly strain to keep going. We started to make the act slicker—the equivalent of East Village gentrification. A performer friend named Bobby Reed had joined us and he was a bundle of new energy. Hired guitarists John and David Rinehimer also made things polished. But the backup girls started leaving, one saying the act had become “gay cabaret” and another one irked that I was angry when she dropped out of a promotional photo shoot to spend quality time with her father. (I was desperately trying to hold the group together, perhaps too tightly.)

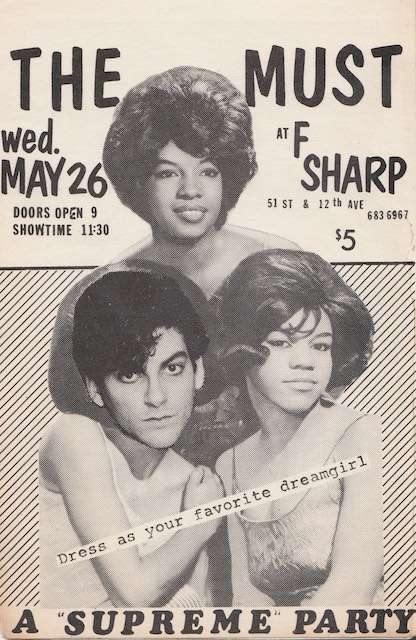

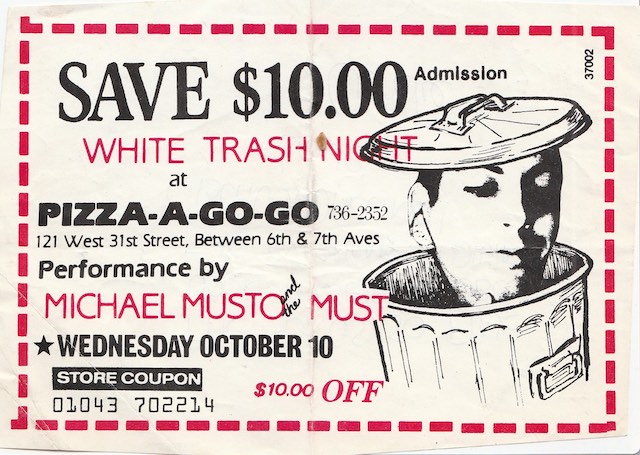

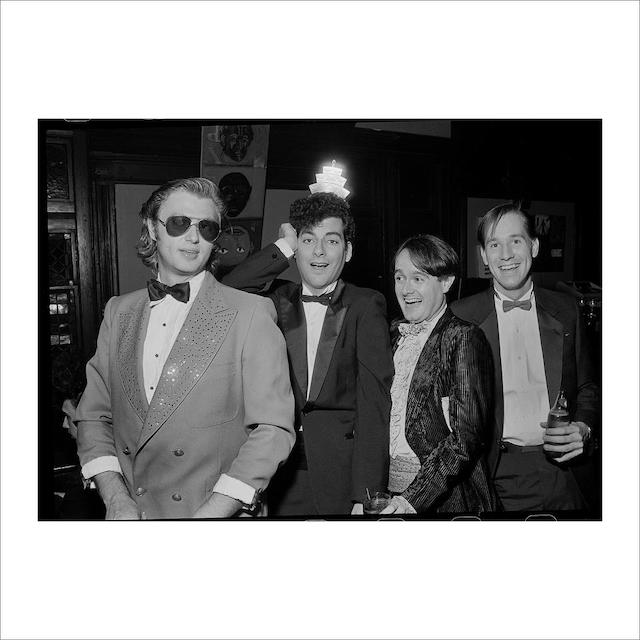

Two other backup singers joined us—Jeff Horn and Bob Moylan—and they were straight, but never homophobic. (They were also great at rehearsing harmonies.) By this point, it was Michael Musto and the Must, which made sense since the Supremes had ultimately become Diana Ross and the Supremes, and I wanted to do everything that they did.

We played a docked boat called the Purple Barge—anything for a gig, and besides, it was fun. We’d played a rally in Central Park, which was thrilling, especially since political correctness hadn’t suffocated everyone yet and no one booed. But every step forward was greeted with a setback, as my life on the Rock and Roll D-List proved alternately giddy and hazardous. For example, things were looking up when we landed a stint in a large New Jersey theater, opening for the Temptations. Yes, I’m talking about the real Temptations (or whatever was left of them at that point). We were beside ourselves, though I wasn’t sure if the booker realized that our act was part loving homage, part high-camp spoof, and I was flamingly gay. Well, sure enough, the gig was canceled with no explanation at all. They must have done a little more research. I ain’t too proud to beg, but I knew things were hopeless, so in despair, I notified the band that we didn’t have to “Get Ready” for this appearance after all.

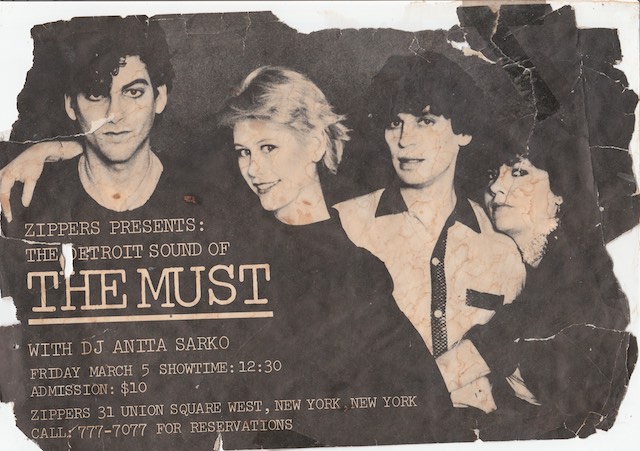

The main problem for me was that, not having anyone I could dole out power to (Mark Busch? I don’t think so), I assumed all responsibility for the group myself. I booked the gigs, reserved the rehearsal room, got the charts done, organized photo sessions, did mailings, took out ads, did postering, handled publicity, and dealt with the club managers. This was pre-Internet, so it was all done via an endless array of phone calls and in-person meetings. And I paid for it all myself! By time I hit the microphone, I was utterly exhausted—and almost broke—but I came alive for the spotlight, adrenalized out of sheer necessity.

And then I would get grief anyway. It hurt my feelings when I showed a backup singer an ad I had taken out to promote a gig and she responded, “Forty dollars wasted.” Huh? You have to advertise! Besides, this was out of my own pocket! When we got paid for the gigs, I paid the hired musicians what they required and divvied up the rest equally among the singers (including myself) and Rhonda. No expense money was taken out of that pay, and I never paid myself a cent more than the others. I lost a fortune!

I also managed to generate press for us, but being a dilettante—I mean a Renaissance man—had its drawbacks, since some people have a hard time taking you seriously when you try to do more than one thing. One magazine review said I could write, but not sing. Another review said I could sing, but not write. I started to wonder if I could do either.

But what mostly broke up the band was the fact that in late ’84, I landed my column in the Voice and that became my primary focus. I still perform here and there, though, and my favorite songs will always be anything originated by Miss Ross. She is the Boss. And I am eternally tickled that my beloved Musts and I put on a show.

–END–

Michael Musto is a columnist, pop cultural and political pundit, NYC nightlife chronicler, author, and the go-to gossip responsible for the long-running (1984-2013) Village Voice column, “La Dolce Musto.”

His work regularly appears on this website as well as Queerty.com and thedailybeast.com, and he is writing for the new Village Voice, which made its debut in April of 2021. Follow Musto on Instagram, via @michaelmusto.

Chelsea Community News is an independent, hyperlocal news, arts, events, info, and opinionwebsite made possible with the help of our awesome advertisers and the support of our readers. Our Promise: Never a paywall, no pop-up ads, all content is FREE. With that in mind, if circumstances allow, please consider taking part in our GoFundMe campaign (click here). To make a direct donation, give feedback, send a Letter to the Editor, or contact our founder/editor, email Scott Stiffler via scott@chelseacommunitynews.com.

To join our subscriber list, click here. It’s a free service provding regular (weekly, at least) Enewsletters containing links to recently published content. Subscribers also will be sent email with “Sponsored Content” in the subject line. That means it’s an exclusive message from one of our advertisers, whose support, like yours, allows us to offer all content free of charge.

You must be logged in to post a comment Login