BY GERALD BUSBY | As I age, and this year I’m celebrating my 86th birthday, it becomes increasingly clear that the degree to which I am willing to be grateful for who and what I am is precisely the degree to which I am willing to be thankful for consciousness itself and my ability to remember.

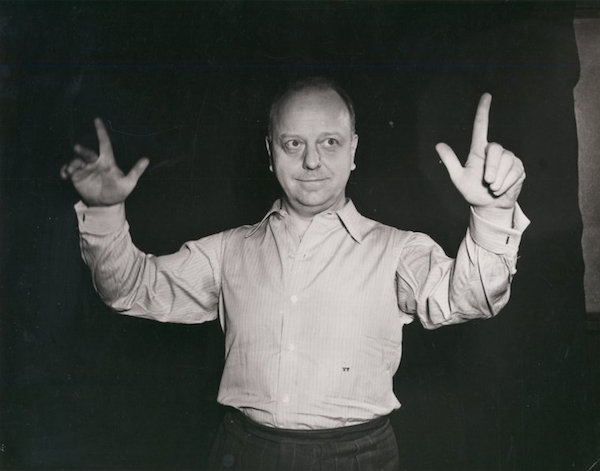

It was from Virgil Thomson, during the 12 years I was his protégé, neighbor, and sous chef at the Hotel Chelsea, that I learned understanding how something worked—its function, its suitability to serve a purpose—was far more important than its meaning. For Virgil, meaning was always arbitrary. “Slaves ask why,” he would say. “Masters ask how.” He never hesitated, however, to let me know exactly what everything meant.

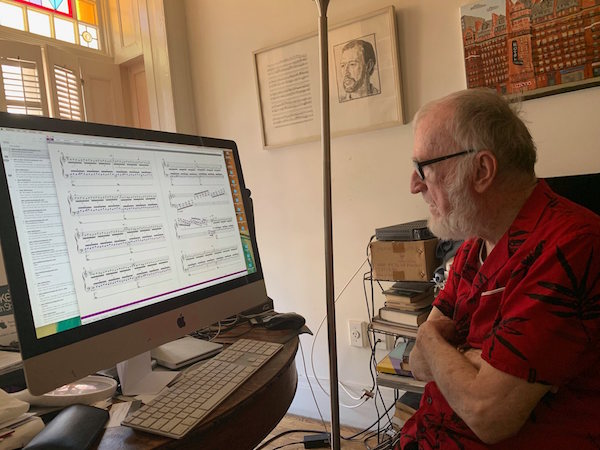

Another thing I learned from Virgil was that what one produces, and is acknowledged by others, is important, not what one thinks is meaningful about one’s own work. This thought came to me especially as I considered what I was grateful for as an old man who had just experienced being close to dying. Number one on that list is my music, specifically the score or 3 WOMEN (writer/director Robert Altman’s 1977 film). When I get depressed, I think that my music, as part of the movie, will endure well beyond my physical existence.

It was only a year ago that I was cursing consciousness, as I lay prostrate on a hospital bed after major surgery to remove my colon. I thought I was dying and hoped death would come soon and without pain. But months of considerable physical discomfort ensued, and I practiced Reiki, a Japanese Zen-Buddhist healing modality I acquired 20 years ago at my HIV clinic. Reiki and mindfulness taught me the value of being still, no matter how I felt. I discovered consciousness itself to be the context of my being, and as such, had no inherent meaning. It was I who made the content of my consciousness significant, made it bearable or unbearable. I chose to suffer and could instead choose not to.

That knowledge was a gift I continue to forget and then rediscover. I wake up to it countless times, always surprised that it’s my choice to be happy, that I’m the source of my own happiness.

Composing music—especially since my near-death experience while recovering from colon surgery—has become, for me, the most spontaneous expression of consciousness. The musical forms that arise from consciousness constitute my daring to create sequences of sounds that resolve themselves in cadences with no implied meaning.

The intuitive pinch that emotion gives consciousness also clouds the mind with thoughts of meaning and expectations, the numberless devices that ego uses to make itself known.

It all comes down to how memorable my music is. Gratitude depends on memory, and the memory of my music must find its place in a consciousness that has no limits.

-END-

Other Articles by Gerald Busby

Composer Gerald Busby and the ‘Conduit of the Keyboard’—August 29, 2019

My Ghosts, My Specters—November 4, 2020

Chelsea Community News is made possible with the help of our awesome advertisers, and the support of our readers. If you like what you see, please consider taking part in our GoFundMe campaign (click here). To make a direct donation, give feedback, or send a Letter to the Editor, email scott@chelseacommunitynews.com.

You must be logged in to post a comment Login